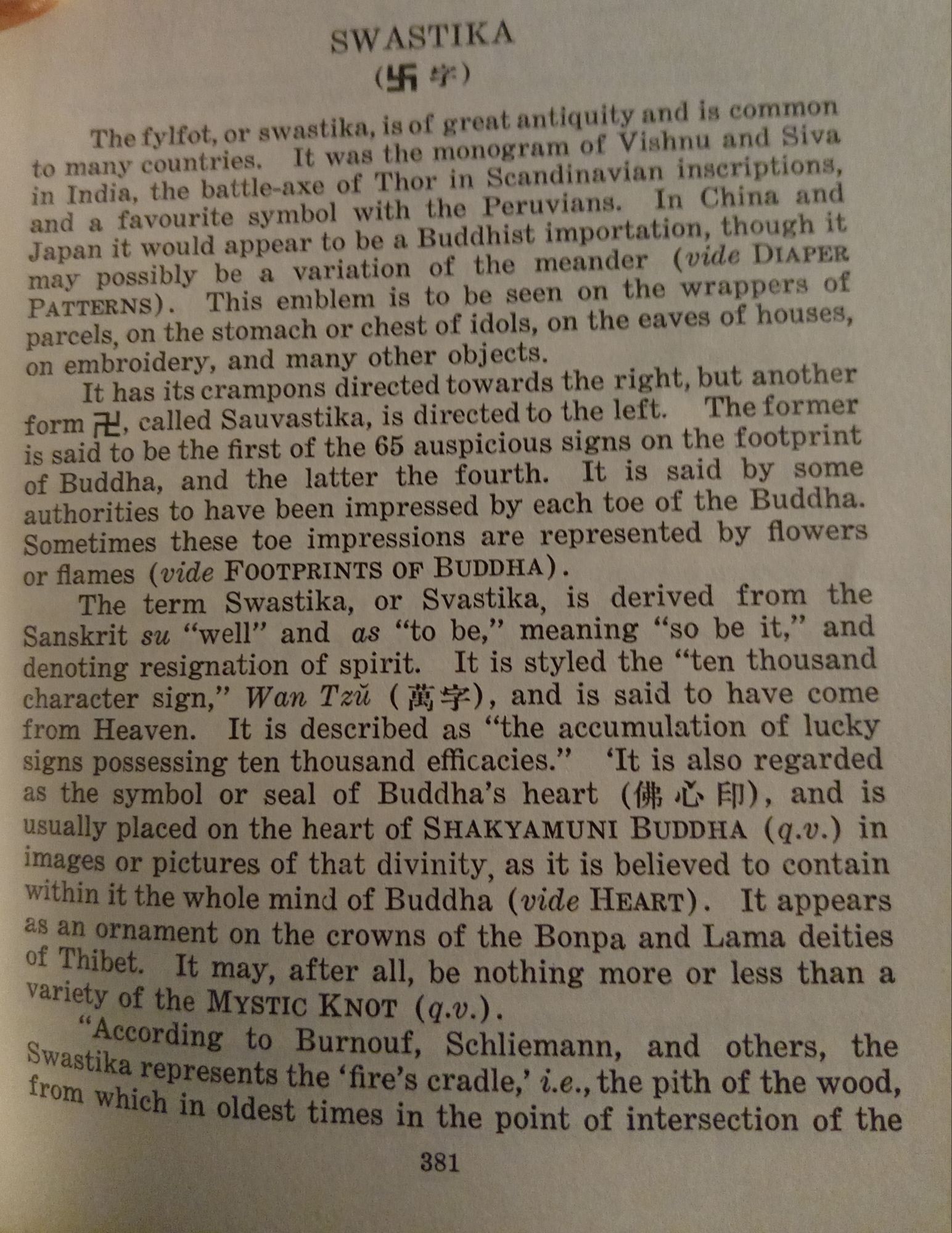

Translator’s Note: I have added the “Swastika” entry from the above Encyclopaedia to complement the data given in the below – Chinese language article. Buddhism may have developed as long ago as the 10th century BCE in ancient India (during the Shang Dynasty in China) – as opposed to the preferred Western dating of 6-5 centuries BCE. Either way, it is believed that Buddhism first arrived in China between the first century BCE – and first century CE. It then developed to around the 6th century CE before it assumed a more or less “correct” structure. Obviously, there is a relationship between the Brahmanical religion and the Swastika as is recorded above – but it is the dating of that relationship that is relevant. Did this relationship occur after Buddhism adopted the use of the Swastika? Was the Swastika imported into India after Buddhism spread to China? A number of Hindu texts are believed to be older than Buddhism – but were in fact written after Buddhism developed and was spread. Indeed, many Hindu texts were answers to the challenge of Buddhism – and were developed long after the Buddha passed away. We must be careful how we view history – particularly as Western governments are quite happy to manipulate narratives. For instance, Hitler never visited Asia but rather came into contact with the Swastika through the distorted teachings of “Theosophy” – and the racist nonsense spouted by Madam Blavatsky and her cronies. Merely assuming a teaching possesses a long history is only a belief – it may well have no bearing in reality. It is interesting that the Swastika and Buddhism are entwined in China – whilst Indian scholars do not know why this should be the case – as there is no obvious historical association between the Swastika and Buddhism known in India. Furthermore, I have not seen the Swastika used in Thailand or Sri Lanka – two Theravada countries. John Ruskin (1819-1900) had Western Swastika (Fylfot) engraved on his grave stone in Coniston (Lancashire). ACW (17.10.2024)

2023-03-27 00:00 Source: The Sorrow of the City Published in: Henan Province

Introduction:

As one of the three major religions in the world, alongside Christianity and Islam, Buddhism has had a profound influence in various countries for thousands of years. Within Chinese history, Buddhism has gradually learned from – and absorbed – the prevailing local Confucianist and Daoist teachings during the Wei and Jin Dynasties (prior to being introduced during the Han Dynasty) – finally becaming one of the three major religions in China.

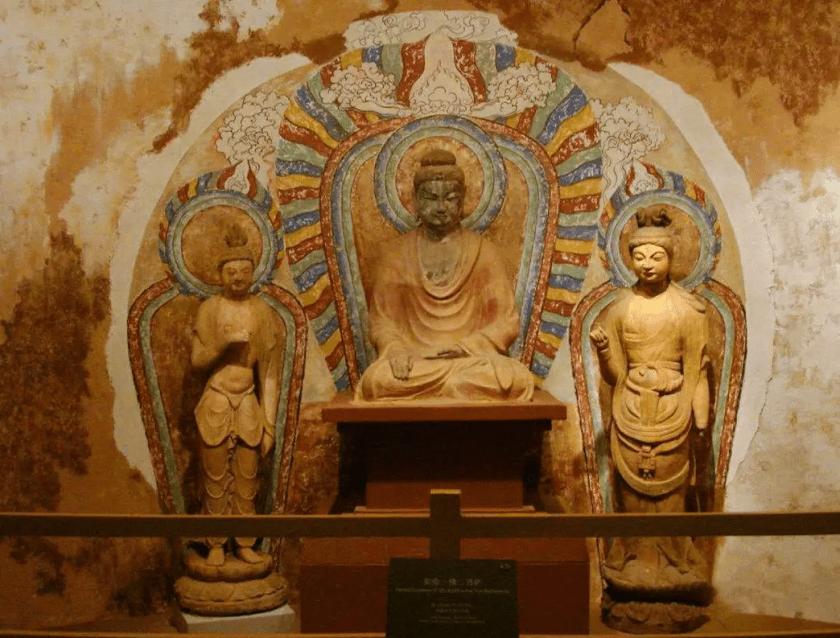

Common Buddhist cultural symbols include Buddha statues, Guanyin statues, lotus and other familiar symbols. But there is another Buddhist symbol that everyone is familiar with, but no one knows what it means, which is the “卍”. We can often see the “卍” on the chest of Buddha statues – and we also know that the pronunciation of this symbol is “万” (Wan) or “Ten Thousand Things” – but why is the “swastika” (Sanskrit) referred to in this way? How did this symbol come into being?

1) For the Chinese people, Confucianism and Daoism are native sects born in the Spring and Autumn Period, while Buddhism is a foreign culture from India introduced into China prior to the Wei and Jin Dynasties, suggesting that the swastika must have been introduced into China at some point during this process – but this is not the case. There are many different opinions about the origin of the swastika, and many of the statements that sound reasonable and well-founded on the surface – do not standup to in depth scrutiny.

Buddhism was not popular when it was first introduced into China during the Han Dynasty. During the later Wei and Jin Dynasties, Daoist metaphysics constituted the mainstream thought of Chinese society. As well as this development, China’s orthodox belief has always been Confucianism. This is because Confucianism’s positive worldly thought encourages people to engage in political and moral practice. The three cardinal guides and five constants stipulated by Confucian ethics can also play a role in stabilizing society. Therefore, it has always been vigorously promoted by rulers.

In contrast, Daoism does not pursue fame, wealth, and honour, ignores worldly splendour and enjoyment, and pursues spiritual tranquility, so it is welcomed by the people. When Buddhism was first introduced to China, it was not loved by the rulers or the people, so there were few believers. It was not until the Tang Dynasty that Buddhism began to be valued by the rulers.

Empress Wu Zetian (武则天) of the Tang Dynasty was attracted to Buddhism very much and often invited Ch’an Masters to the palace to explain Buddhist Sutras to her. It was under the promotion of Wu Zetian that Huayan (华严) Sect became a major Buddhist school during the Tang Dynasty.

At that time, there was still no consensus on the pronunciation of “卍” within Buddhism. Some people insisted that it should be pronounced as “万” (Wan4) or “The Ten Thousand Things” – but others opposed this interpretation – and believed it should be pronounced as “万”(mo2) or “Scorpion” – referring to an Oracle Bone Inscription which refers to a non-Chinese primitive tribe (during the Shang Dynasty) that worshipped the “Scorpion” whilst mimicking its movements in a ritualistic dance (perhaps implying the “foreignness” of India).

Finally, it was Empress Wu Zetian who issued an Edict declaring the pronunciation of “卍” should be “wan4” or “Ten Thousand Things” – and criminalising any other interpretation. This ended the dispute about the pronunciation of “卍” (wan4). To this day, the pronunciation of “卍” in China is “万” (wan4) – or “Ten Thousanf Things”.

2) The Origin and Development of the “卍” (Swastika)

Although Empress Wu Zetian’s Edict stipulated the official pronunciation of the swastika, Buddhist believers and archaeological researchers in later generations – are still studying the origin of the swastika.

Early humans did not possess writing – this fact is now well-known. People in primitive society used symbols to record events in life. Various symbols were later simplified and organized into a coherent system to form writing.

The swastika can be regarded as a symbol – or a special character. Therefore, exploring the origin of the swastika is of great significance in the understanding of the development of folk culture and the study of its archaeology. Tracing the origin of the swastika can not only examine the process of foreign culture entering China, but also explore the origination of text in primitive society.

Some scholars believe that since the swastika is widely used in Buddhism, as a foreign culture, the swastika must have been introduced into China with Buddhism. If this inference is followed, the swastika was born in ancient India, and after being introduced into China, it underwent local evolution before acquiring the interpretive pronunciation of “万” (wan4).

Unfortunately, Indian Buddhist researchers have studied the history of Buddhism in India and found that there is no definite conclusion regarding the origin of the swastika in India.

As a symbol, the swastika can be considered to represent a word or a geometric figure. As a word, the swastika did not have any meaning before the birth of Buddhism. As a geometric figure, the swastika is not special in Indian culture. Therefore, we cannot conclude that the swastika was born within Buddhism just because it is now a symbol exclusively associated with Buddhism.

Just like the lotus, before Buddhism was introduced to China, the lotus was an ordinary aquatic plant. After Buddhism was introduced to China, the lotus was given sacred significance as the meditation seat of the Guanyin Bodhisattva.

3) What is the Difference Between “卍” and “卐”?

Although the swastika is regarded as a symbol exclusive to Buddhism, there is no chapter explaining the origin and history of the swastika in the Sutras of Ch’an (禅), Tiantai (天台), Huayan (华严) and other Buddhist sects. The Buddhist Sutras only explain that the meaning of the swastika is a symbol of auspiciousness, beauty and perfect morality.

Therefore, some Indian researchers believe that the swastika is a symbol that was born in Europe and/or Central Asia in the times before Buddhism. Only later was the swastika introduced into the Far-East and absorbed by Buddhism – becoming the exclusive symbol of Buddhism in the Far-East.

This statement has archaeological evidence. Pottery artifacts unearthed from ruins in Central Asia have symbols very similar to the swastika. These artifacts date back to about 4,000 years ago, far earlier than the 2,500-year history of Buddhism.

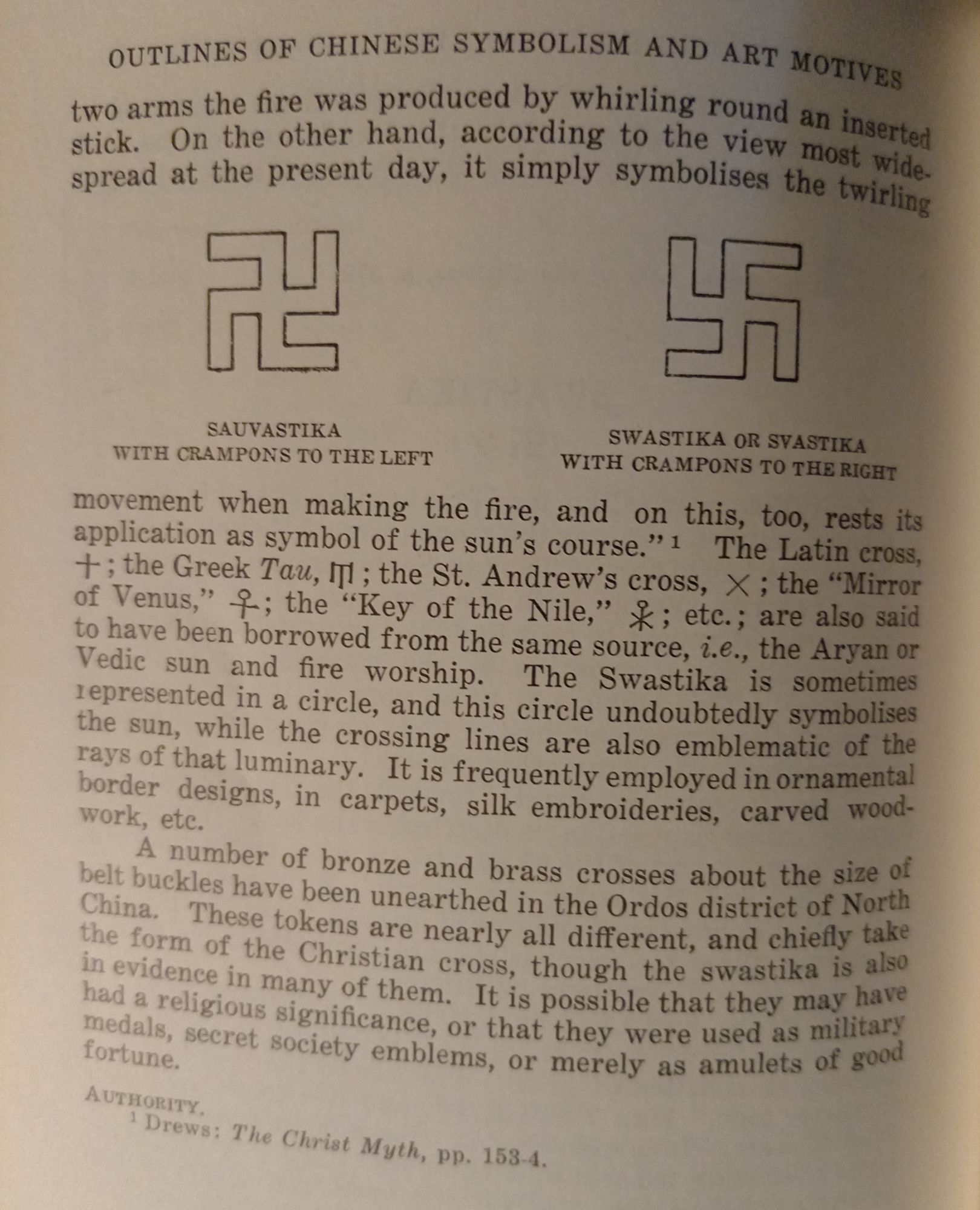

Coincidentally, there is another symbol in Europe that is almost identical to the swastika, but this symbol does not have the Buddhist compassion and kindness to save all living beings.

This symbol is axially symmetrical with the swastika – whilst the direction of the spiral is opposite to that of the swastika. It represents a dark, cruel and bloody history in Europe and even the whole world. This symbol is the Hitlerite swastika “卐” – the symbol of the Nazis.

Strictly speaking, the Nazi swastika is not like the “卍” – where all straight lines are perpendicular or parallel to the horizontal line, but are tilted 45° clockwise.

The similarity between 卍 and 卐 can only show that the birth of human symbols and characters is somewhat accidental. From the perspective of geometry, the two symbols are symmetrical to each other, but from the perspective of human history, the difference between the two symbols is huge.

Although both are pronounced as “wan”, the Buddhist swastika represents great compassion and the kindness through saving all living beings, while the Nazi swastika represents the greatest disaster and the most tragic war in human history. As one of the three major religions in the world, Buddhism has many believers. Some believers went to Europe for tourist reasons – and were arrested by European police because they wore a necklace with a swastika jade pendant engraved on it!

The police mistook the Buddhist for a Nazi. According to the United Nations Charter, the Nazis are regarded as representing an anti-human extremist terrorist organizations by all countries in the world = this has been the case since World War II. Therefore, we must pay attention to distinguishing swastikas in our daily lives and never make mistakes or cause unnecessary trouble to ourselves.

Conclusion:

As a symbol of Buddhism, the origin of the swastika is unclear. We only know that the pronunciation of the swastika was stipulated by the Tang Dynasty Empress Wu Zetian, but earlier, there was no general consensus on the pronunciation of the “卍” symbol.

Today, the swastika, as a symbol of Buddhist culture, is widely used in Buddhist architecture, books, and decorations. When we see the swastika, we need to be careful to distinguish it. The swastika is the symbol of Buddhism, not the symbol of another international (illegal) organization that uses a symbol very similar to the swastika (“卍”).

Chinese Language Source:

https://www.sohu.com/a/658619099_121478894

佛教的“卍”这个字怎么读?其实背后大有学问,别闹笑话

2023-03-27 00:00 来源: 倾城之殇 发布于:河南省

引言:

佛教作为和基督教,伊斯兰教并列的世界三大宗教之一,千年以来在各个国家都具有深远的影响力。在中国的历史上,佛教自从魏晋传入后逐渐和本土的儒家,道家互相借鉴吸收,最终本土化成为中国的三大宗教之一。

常见的佛教文化象征有佛像,观音像,莲花等人们熟悉的标志物。但还有一种大家都很熟悉,却不知道到底有什么含义的佛教标志,这就是“卍”。

我们经常可以在佛像的胸前看见“卍”,也知道这个标志的读音是“万”,但为什么卍字会是这个发音?这个符号又是如何诞生的呢?

1.卍的读音到底是什么

对我们中国人来说,儒家和道家是诞生于春秋时期的本土教派,而佛教则是魏晋时期才传入中国的外来文化,因此卍字肯定也是一起传入中国的。但事实并非如此,卍字的来历众说纷纭,很多听起来有理有据的说法都并不严谨。

佛教刚刚传入中国后并不受欢迎,魏晋时期,道家玄学是社会的主流思想。中国的正统一直都是儒家,这是因为儒家积极的入世思想鼓励人去从事政治实践道德实践,儒家伦理规定的三纲五常也能起到稳定社会的作用,因此一直以来都受到统治者的大力推广。

与此相对的是道家以不追求功名利禄,无视尘世的荣华富贵和享受,追求精神的宁静,因此受到民间的欢迎。而佛教刚刚传入中国的时候即不受统治者的喜爱,也不受民间的欢迎,因此信徒很少,直到唐朝佛教才开始被统治者所重视。

唐朝的女皇武则天非常喜欢佛教,经常请禅师入宫来为她讲解佛家经文,华严宗就是在武则天的推广下成为了唐朝的一大佛教宗派。

当时佛教内部对卍的发音仍未统一,有人坚持应该读作四声的wan,但还有人反对,应该读作二声的de。

最终是女皇武则天下令,卍的发音就是四声的wan,别的说法一律视为谬误,这才结束了关于卍的发音的争端,一直到今天,卍在中国的发音都是“万”。

2.卍的起源和来历

虽说女皇武则天的圣旨是规定了官方的卍符发音,但后世的佛教信徒和考古研究者依然在研究卍的来历。

我们都知道,人类最初是没有文字的,原始社会的人用壁画或者符号来记录生活中发生的事件,各种符号经过简化之后整理成体系才形成了文字。

卍既可以被视为符号,也可以被视为一个特殊的字。因此探究卍的起源,对民俗文化和文字考古研究有着非常重大的意义。追溯卍的来历,既可以考察外来文化进入中国的过程,也可以发掘文字在原始社会诞生的契机。

部分学者认为,卍既然被广泛的应用于佛教,那佛教作为外来文化,卍字符肯定也是跟随佛教一起传入中国的。如果按照这种推断,那卍字符就是诞生于古印度,被传入中国之后经历本土演化之后才变成“万”的发音。

遗憾的是,印度本土的佛教研究者考察了印度自己的佛教历史,发现卍字在印度的起源也没有什么确凿的定论。

卍作为一个符号,既可以被认为是文字,也可以被视为一个几何图形。如果作为文字,卍在佛教诞生前不具有任何文字的指代意义。如果作为几何图形,卍在印度文化中也没什么特殊性。我们不能因为现在卍是佛教的专属符号,就认定卍诞生于佛教。

就像莲花一样,在佛教传入中国之前,莲花就是一种普通的水生植物,佛教传入中国之后,莲花才作为观音菩萨的禅座被赋予神圣的意义。

3.卍和卐的区别

卍尽管被视为佛教专属的符号,但在禅宗,天台宗,华严宗等佛教派系的经书中都没有任何解释卍的起源与来历的篇章,佛家经书只解释了卍的意义是吉祥美好,圆满道德的象征。

因此,还有部分研究者认为,卍应该是早于佛教之前就诞生于欧洲或者中亚地区的一个符号,后来才传入东方被佛教吸收,成为佛教的专属象征。

这种说法是有考古依据的,在中亚地区的遗迹中发掘出来的陶器文物,上面就有和卍非常相似的符号,这些文物的年代在大约4000年之前,远早于佛教2500年的历史。

巧合的是,在欧洲还有一个几乎和卍一模一样的符号,这个符号却没有佛教慈悲为怀,普度众生的善意。

这个符号是卍的轴对称,螺旋的方向和卍相反,代表的是欧洲乃至整个世界上一段黑暗,残酷而又血腥的历史,这个符号就是卐,纳粹的标志。

严格来说,纳粹的卐并不像卍一样,所有的直线都和水平线方向垂直或者平行的,而是顺时针旋转45°倾斜。

卍和卐的相似性只能说明人类的符号和文字诞生有一定的偶然性,两个符号从几何学的角度看,就是互相对称的关系,但在人文历史的角度上看,两个符号的区别可就大了。

尽管发音都是“万”,但佛教的卍代表的大慈大悲,普度众生的善良,纳粹的卐代表的则是人类历史上最大的灾难,最惨痛的战争。佛教作为世界三大宗教,具有很多信徒,有的信徒去欧洲旅游,因为戴反了雕刻有卍字玉佩的项链,遭到了欧洲警察的抓捕。

警察误以为这名佛教徒是纳粹主义者,根据联合国宪章的规定,纳粹自从二战之后就被全世界所有的国家视为反人类极端恐怖组织。因此我们在日常生活中一定要注意区分卍,千万别搞错了给自己引起不必要的麻烦。

结语:

卍作为佛教的标志,来历没有明确的出处,我们只知道卍的发音是唐朝女皇武则天规定的,但在更早的时候,卍的发音并没有什么普遍共识。

如今,卍作为佛教文化的符号,被广泛应用于佛教的建筑,书籍,装饰品中,我们看见卍需要注意区分,卍是佛教的标志,而不是另一个和卍很像的国际非法组织的标志。