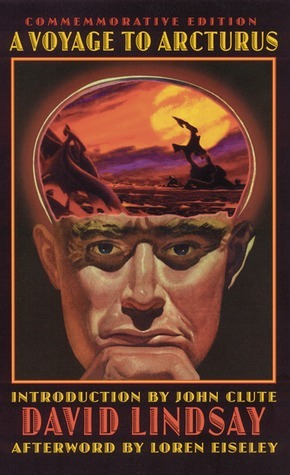

Oh yes – David Lindsay’s “A Voyage to Arcturus” (1920!). Well, I first encountered the name “Arcturus” whilst visiting Totnes probably about 2005 – it could have been earlier – but no earlier than 2002. This is a bookshop that trades in unusual as well as commercial spiritual and religious books and magazines – usually Eastern – but includes various types of Christianity, including the Gnostic, Monastic, Celtic, and Orthodox, etc. Posters adorn a wall advertising Taijiquan, Qigong, martial arts classes, meditation, and various other self-help and self-improvement systems and ideas. It is a special place of instant mind expansion – but of course – special offers aside – things are not always cheap. This is the way it is in a capitalist society – transcending capitalism is itself a lucrative business. Needless to say, in “A Voyage to Arcturus” material reality (unlike the Tones Fore Street) is not set in concrete (pun intended). Furthermore, reality is described as “plastic” and in continuous (potential) flux. I think this might be of interest to the Trans community. Trans is not “new” as the reactionary right keeps trying to assert.

I first thought the name was “Arthurian” – alluding to King Arthur (who I happen to think was real and very great Celtic King) – but I was told “NO” – this name derives from a masterpiece of science fiction penned by the Londoner – David Lindsay (1876-1945). He died from a tooth abscess that turned into gum cancer (clean you teeth and get infected teeth “pulled” to save your life). He was from working class stock but was so clever that he earned a scholarship to University – but in those days University was only for the wealthy middle and upper class. Even with a scholarship – his family could not afford to let him go to University. However, Loyds of London was informed of his academic abilities and immediately employed him as an Insurance Clerk – a very well paid middle class profession.

This move effectively lifted his family out of relative poverty (they were upper working class) and allowed his parents to move around the country freely following various pursuits – even settling in Scotland for a time (his father was Scottish and David did spend some of his youth in the Scottish Borders). Remember, this was from the time of strict “class” division in the UK. Workers were members of Unions, demanded Socialism, and voted Labour. The middle and upper classes believed in bourgeois individualism, free market economics, and voted Tory or Liberal. The distinctions were clear and overt (today they are hidden and mysterious like the Freemasonry that controls it). When war broke-out in 1914 – David Lindsay was already 38-years old and considered too-old for frontline service in the British Army.

However, he was the right age for a strategic reserve that could protect the UK Mainland – and as he was in a middle class profession – he was conscripted into the elite Grenadier Guards. Again, background and class matter. He was not given an Officer’s Commission because his family were working class (and considered physically and psychologically unable to lead) – but he was allowed to serve as a “Guardsman” (a “Private”). Having completed Basic Training – he was rewarded with the perk of either staying in the Grenadiers – or transferring to another Regiment of his choice. As a pen-pushing bureaucrat (something like an Accountant) – Lindsay chose to transfer to the Royal Army Pay Corps – which dealt with the pay for millions of men.

He was married in 1916 and left that Army in 1918 – moving to a remote part of Cornwall – where he wrote the above mentioned masterpiece. I have spent many isolated retreats in the beautiful Cornish countryside and I can see how it may have inspired the kind of “disconnect” with the capitalist system he inhabited. Let’s face it, money is the essence of predatory capitalism and Lindsay spent much of his younger years directly associated with it. Perhaps his imagination screamed for release. Perhaps his proletariat essence demanded a release from the straitjacket of conformity his academic success trapped him within. The reason for his brilliance could be any number of factors. His Publisher demanded that 30-pages (15,000 words) be removed before the book could be published. Although a commercial failure at the time – today it is considered an absolute masterpiece.

What was written on those 30 missing pages? No one knows because they remain missing. It is interesting to speculate as what is left reads like the music (and lyrics) from “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Considering how bizarre and sexually suggestive the remaining content is – one is left pondering as to the true scale of non-conformity. Anyway, a number of early SciFi writes used the agency of “sleep” as a means to travel long distances or indeed travel through time – I think this idea dates back to the French author “Louis-Sébastien Mercier“ (1740-1814) and his 1771 masterpiece entitled “The Year 2440: A Dream If Ever There Was One” (L’An 2440, rêve s’il en fut jamais). I think HG Wells also borrowed this concept for his 1898 book entitled “When the Sleeper Wakes“. Lindsay, it must be said, did flesh it out somewhat by suggesting it was possible to “travel on light beams” in “torpedo-shaped metal space craft” (the essence of the modern “Alien” franchise?). Of course, it must be stressed that Arcturus was in fact the “sun” around which the planet Tormance orbited. The protagonists did not travel to the sun – but to the planet Tormance – which is an interesting and unexplained contradicting. Why not the title “A Voyage to Tormance” – as this planet seems far more warmer than earth (the main character Maskull required a blood transfusion to just survive – provided wilfully by a Tormance women (an allusion to the power of menstruation – perhaps?)

The journey to Arcturus was a mere 37 light years – which is rather modest by today’s standards – when you think about it. Many describe Lindsay’s imaginations as something akin to a LSD trip – so detached were they from the norms of everyday life the early 20th century Britain. How did he manage to change the thought processes of his readers with just the arrangement of words on a sheet of paper? When bowled down to its bare-bones – Lindsay is moving the pen in a very similar light to that of Chaucer and Shakespeare. His words possess the potential to influence change in the world and break apart the capitalist status quo through the mere agency of “word arrangement”. In this regard, I am reminded of Jacques Derrida’s “Writing and Difference“. It is a very similar ability to that demonstrated by Karl Marx. Meaning, when expressed adequately or appropriately, can change mind-sets and alter behaviour patterns.

And to keep the Marxists happy “alter behaviour patterns – and change mind-sets” as Marx quite rightly pointed out that the bourgeoisie “invert” reality to keep control of society (this is true of every aspect except science – but even then the permitted scope is carefully limited). One reviewer describe Lindsay’s work as “Tripping Balls” – and I suppose he is right. But Lindsay was not on any kind of drug as far as we know – and is reported as being a “very boring and predictable fellow” by those who knew him. My question is – “did he read Marx?”. I ask this as the works of Marx alter one’s perception here and now – so that the reader is never the same. If he never read Marx, I think his impostership in the middle class world – when he was a working class man – created the dialectic tension that led to his wonderfully textured – and yet oddly “flat” – presentation (this describes my life exactly).

One aspect that stands-out is that women in Arcturus are “free” and “dominant” in a manner not yet known in the UK at the time (despite the service of women during WWI). He seems to understand evolutionary theory exactly – allowing for “new” senses that “cognise” as of yet “unknown” perceptual data. It has been suggested that reality on earth might well be far more “textured” than our evolved senses allow us to know. Where did Lindsay get this idea from? It is a remarkable insight – as evolutionary theory at that time was nowhere near as developed as it is today. Material science in the early 20th century was still trying to throw-off the shackles of centuries of theological domination. Somehow, Lindsay’s proletariat mind was emanating the imaginative superiority that Marx suggested the working class possessed due to the disciplined physical and mental discipline the mind and body has been subjected to since the Industrial Reolution.

The factory is like a military barracks strictly controlled by the moving-hands of a central clock. Of course, Lindsay used his intellect to swap the factory for the office – but the reality remains much the same despite the airs and graces associated with the latter. When I review the texture of the dialogue, although their obvious Spiritualist and Theosophy influences (including Schopenhauer’s grasp of Buddhism) – I also see a kind of Kafka-esque- “alienation” at work in as much as the earth characters are permanently inhabiting a state of “detachment” from the physical world that surrounds (their now expanded) senses. Not only are all things “unfamiliar” – but there is more to be “unfamiliar” about. Was Lindsay saying “Nothing is certain” decades before Heisenberg? Lindsay managed to write a fictional work that is profoundly (dialectically) “unstable”. This is a positive aspect that drives a wedge into the fabric of bourgeois certainty – or that which maintains the oppression to experience everyday of your life. No wonder Lindsay’s work was oppressed as soon as it appeared not long after the 1917 Russian Revolution and the defeat of the UK and US military forces that had invaded Russia – which was unfolding at that time (the defeated Western military forces would be fully withdrawn in 1921 – after causing 10.5 million Russian deaths).