For over a century, the sweet aroma of freshly-baked biscuits was scented backdrop to thousands of families living around Bermondsey

Southwark News by Herbie Russell 12th January 2025 in History+

In 1889, a biscuit factory magnate made the novel decision to hire a dentist to look after his workforce. In that year alone, 1,053 rotten, infected and wonky teeth were plucked from employees’ mouths.

In an era characterised by miserable working conditions, poor pay, and cold, absentee factory owners, it was an impressive move from the Peek Freans’ biscuit factory.

Since then, much has been made of the factory’s philanthropic credentials. But just how good did those employees have it? Was it the workers’ paradise those Victorian bosses would have us believe? Or do these sweet stories conceal a truth that is harder to stomach?

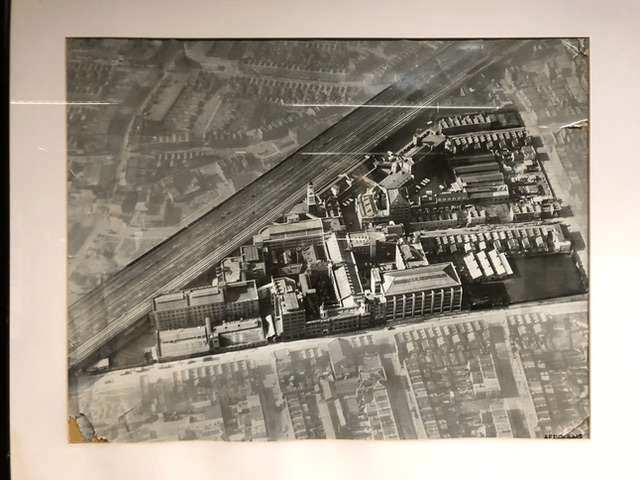

Peek, Frean & Co, Ltd, the birthplace of beloved treats like the Bourbon, the Garibaldi and Twiglets, was founded in 1857. What began as a small start-up at a disused sugar refinery in Dockhead quickly expanded to take on a vast 10-acre site in Bermondsey.

The factory enforced some pretty restrictive rules on workers early on. Women were employed from as early as 1864 but were forced to resign when they became married. After that point, factory bosses clearly felt they belonged in the home, and not on the grimy factory floor. As recompense, the women would receive a special bridal cake. The longer they had worked at the factory, the taller the cake.

Meanwhile, staff could expect the same gruelling hours being worked across Victorian London. 72-hour weeks were the norm and would not change for another 35 years.

But historians always warn we should not judge the past by modern standards. “The historian must not make the mistake of judging the past by modern standards. He must understand, not condemn,” G.R. Elton wrote in The Practice of History (1967).

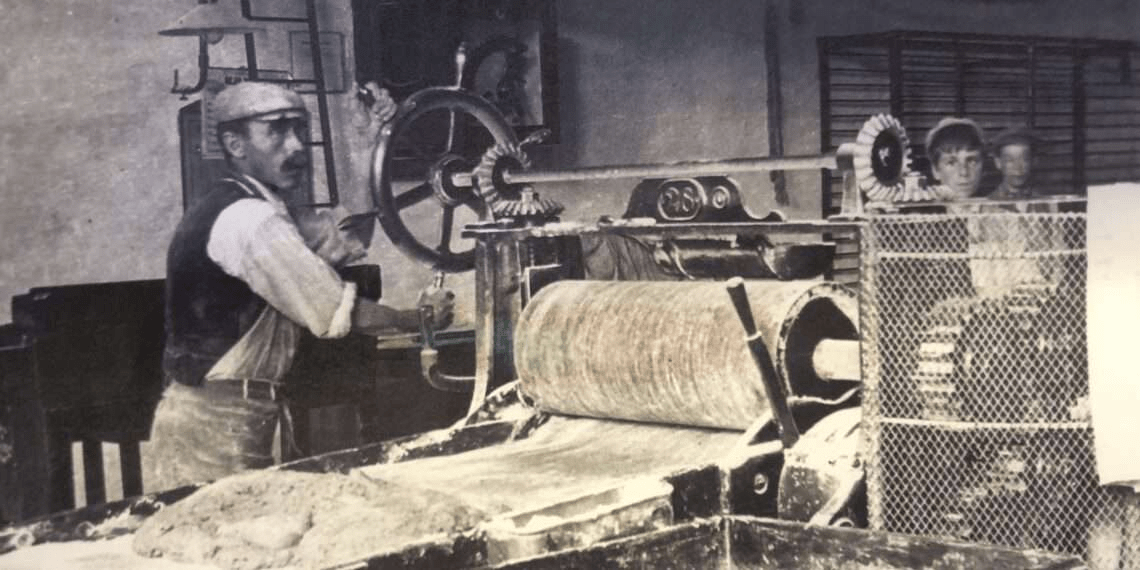

After all, this was a factory trying to stay afloat amid a hugely competitive Victorian manufacturing industry. Salesmen, made to wear top hats to keep up appearances, were being sent out with a horse and carriage to sell their wares to shopkeepers. Peek Freans was doing whatever it could to get a slice of the market before it was too late. And arguably, it was not long before the biscuit factory bosses were going above and beyond to please their workers.

One of the earliest signs of their good intentions was the sports teams they started up. In this aspect, the business was following in the footsteps of other rising manufacturers like Cadbury’s and Rowntrees which were adopting what has since been described as ‘paternalistic capitalism’. In the Midlands and York, these companies were establishing huge housing complexes for workers and their families out in the open countryside. Well aired, and clean, they had all sorts of amenities – medical, sporting and leisure-related – on offer.

There was evidence of this attitude on the Bermondsey site. Though they did not tend provide housing, sport was seen as a worthwhile investment. The factory had its own cricket team from 1894 and the Sports Association was founded in 1903.

Even the women had their own cricket team. Sir Jack Hobbs, England’s foremost cricket star of the era, would even come down from the Surrey team’s home at the Oval to coach them from time to time. The factory owner was happy for the women to wear trousers on the field but this raised eyebrows in London’s wider sporting community. So much so, that amateur historians believe Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) made them swap them out for skirts before they could play competitively.

There was football, golf, bowls, and tennis, much of it played on the factory’s dedicated sports grounds in Lee, south east London, now belonging to Colfe’s School. It wasn’t just amateur athletes being catered for. There was a horticultural society, flower shows, a photography club and a library on site.

Frank Turner, who worked in the factory’s fire brigade for 29 years, fondly remembers representing a factory club at a tournament in the Netherlands in the ‘70s.

Now curator at the Peek Freans Museum, he said: “We went out in 1969 and they came over to play us in 1970. I had my retirement party with the Peek Freans hockey players and the Dutch players in Holland!”

In 1872, the working day was reduced from 72 hours per week to roughly 50 – nine hours per day with a half day on Saturday. Employees, who numbered around 300 at that time, were so pleased they gifted the three directors a gilt silver pen as thanks. While legislation already limited the hours worked by women and children, this universal reduction in working hours was ahead of its time.

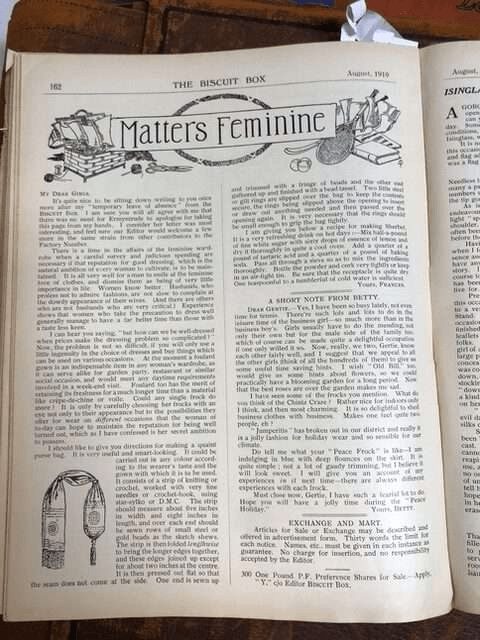

The first female clerks, responsible for typewriting invoices and the telephone exchange, were employed in 1885. The new hires may have been surprised to find the company brochure had a dedicated ladies’ section called ‘Matters Feminine’. However, the suffragettes would not have been too impressed with its content. Topics mainly included cooking, family and fashion.

‘It is all very well for a man to smile at the feminine love of clothes, and dismiss them as being of very little importance in life. Women know better. Husbands, who profess not to admire fashions, are not slow to complain at the dowdy appearance of their wives,’ read one passage.

In the following decades, many of the women employed found promotions were very much possible. Anne Edwards, who got a job as a clerical assistant in 1957, wrote: “Brilliant employers, they paid for me to attend Pitman’s College to extend my shorthand skills. They monitored my progress, my typewriting skills and promoted me from junior to manager’s secretary in the same department. I loved working there.”

In 1899, the factory hired its own dentist and chiropodist. The dentist extracted 1,053 teeth in the first year. Workers were also given a suggestions box where they could deposit proposed changes to factory life and processes. If the suggestion saved the company money, they could be in for a cash reward. For example, when biscuit packets were sealed in the 1930s, the wrapping would often come unstuck and be disposed of. One woman suggested that, rather than binning the packaging, using a strip of sellotape to stick it back down. The factory soon saved £1,000 annually and she received a five per cent cut of the proceeds.

Workers were also rewarded for their loyalty. Prizes for long-serving staff included silver spoons and an ornate clock after forty years, one of which, dating back to 1900, is displayed in the museum.

“They were good. With the suggestion schemes and things like that. They would listen to you. Let’s put it that way,” Frank said.

As in any workplace, mischief was sometimes necessary to pass the time. Yvonne Fowler wrote: ‘As a kid, I always preferred Mrs Peek’s puds to mum’s homemade. However, dad confessed that they had competitions on how high the puddings would bounce when dropped down the stairwell.’

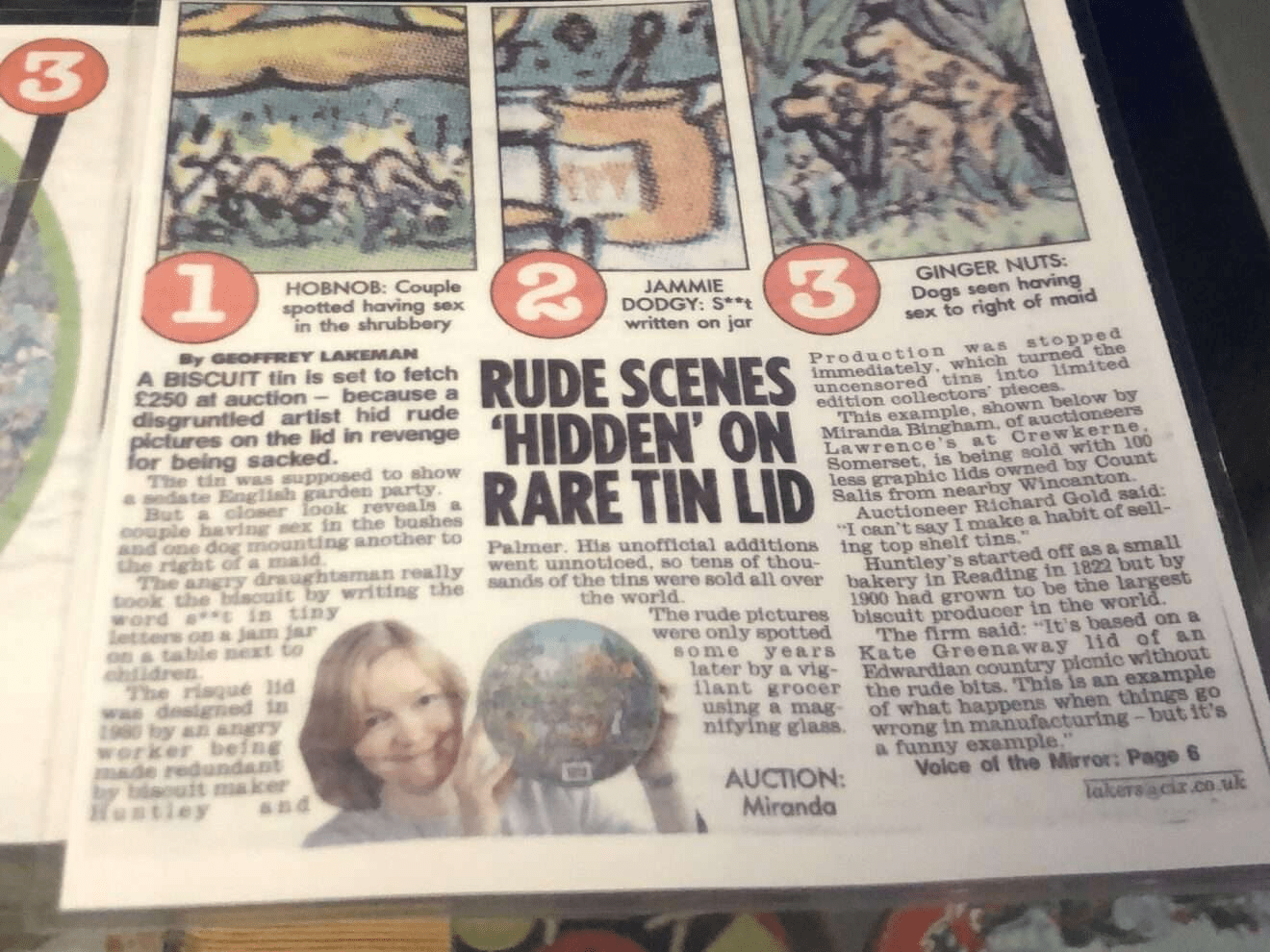

Gary Maygold, curator at the Peek Freans Museum, was even contacted by a woman who had kept her handwritten warning from her boss for having a snowball fight in the workplace. The fact it had enough sentimental value for her to keep decades later was testament to the good time she must have had there, he said. Another memorable story is that of a disgruntled worker who painted rude scenes into some of the more ornate biscuit tins. In 1980, upset at being made redundant, he managed to sneak a couple having sex, swear words and copulating dogs into an otherwise serene garden scene.

Christmas was always a special time in the factory. Patrick O’Grady wrote: ‘I used to taste test the Christmas puddings from the line every morning at 10 AM when I was in the R&D department at Peek Freans. we always had some brandy butter at Christmas time to make it extra special.’

A Works’ Committee, a forum for employees to air grievances, was established in 1918. In the mid-1950s, amid a post-war Labour shortage, staff were polled on whether to let Caribbean arrivals work at the factory. We do not know the results of the poll, but the Works Committee agreed to allow them to work in certain departments. In 1955, the committee’s first Black member – Mr C Laws, was elected to the board.

By the late 19th century, “paternalistic capitalism”—where employers took an active role in their workers’ welfare—was gaining traction among forward-thinking industrialists.

Companies like Cadbury (Bournville) and Lever Brothers (Port Sunlight) were at the forefront of this movement, establishing entire villages for their workers. These developments went beyond workplace initiatives, providing housing, healthcare, education, and recreation. By contrast, Peek Freans’ measures, while commendable, were less ambitious. Without dedicated housing or expansive welfare programs, the factory’s initiatives were largely confined to workplace-based activities.

Peek Freans’ approach to inclusion and diversity also warrants scrutiny. While the election of the factory’s first Black Works Committee member, Mr. C. Laws, in 1955 marked a milestone, the broader context of how Caribbean workers were integrated—or restricted—into the workforce tells a more complicated story. The mid-20th century labour shortage made such hires a necessity, but allowing workers of Caribbean descent into only certain departments suggests lingering biases. The 1950s poll on whether to employ these workers also underscores the conditional nature of their acceptance.

The limits of the factory’s goodwill came into sharp focus in the summer of 1911 in what would become known as the Bermondsey Uprising. Thousands of women downed tools and walked out of factories in Bermondsey and Rotherhithe in protest against “appalling” working conditions and pay.

The women’s strike saw 12,000 workers walk out of factories on the first day, including from the Biscuit Factory. Eventually 14,000 marched to a demonstration at Southwark Park, where famous faces such as suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst spoke.

The strike could not have happened without Ada Salter, Bermondsey’s first female councillor, elected in 1909, and her friends Mary Macarthur, who set up the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), and Eveline Lowe, who was the first woman elected chair of London County Council.

“It was an age that was actually worse for women than the previous ones because of Victorian hypocritical morals,” historian and author Graham Taylor explained to Southwark News.

“They were actually worse off because of industrial revolution which forced them into machinery jobs, whereas 200 years ago in women’s industry they used to do basket weaving at home and they had skilled jobs and got money in. This factory work was not like factory work now. There were no trade unions and that meant the conditions were appalling.”

He said the Biscuit Factory wasn’t “as bad as some others” but remained places plagued by dangers and long hours for little pay. In August, 12,000 women walked out and all the factories came to a halt,” said Taylor.

“What happened was the women had become aware that if they came out on strike they would not be without assistance. Ada set up food depots and kitchens all along the river right from London Bridge down to Woolwich to help the dockers and the women,” Graham said. The strike, which lasted weeks, saw an increase in wages in all of Bermondsey and Rotherhithe’s 20 to 30 factories.

Edward Said, a renowned historian wrote ‘History is always written in the present tense, but it is also always written as though we are trying to make the past conform to the present, so that it becomes acceptable, meaningful, and reassuring,’ in The World, the Text, and the Critic (1983). That is the tight-rope everyone walks when looking back at the Biscuit Factory.

Speak to locals, and many will conjure up wonderful images of the factory, regardless of whether they worked there. Many are undoubtedly influenced by the sweet bakery smells that coloured their childhood thanks to the Peek Freans. Sweet aromas wafting through playgrounds, into classrooms and across parks provide a scented backdrop to halcyon days of ‘simpler times’. Peter Webb wrote: ‘You could walk around Bermondsey blindfold and know where you were by the smell. Peek Freans’ was one of the nicer aromas.’ Many will remember mums and sisters bringing home bulging bags of broken biscuits, much to the delight of their families.

132 years after the business began, the biscuit factory closed on May 26, 1989. While its history may have been complex, with workers fighting for their rights at times, the factory clearly played an important role in the lives of many locals families, putting food on the table, and giving the community a focal point. In a world of unstable work, this should never be sniffed at.

The Peek Freans’ Museum is based at 100 Drummond Road, Bermondsey, London.