Blogger’s Note: This post is in response to the ludicrous idea that Canada should stop being an independent sovereign State – and acquiesce to becoming the 51st State of a Trump-run USA! I respect the fact that Canada has been loyal to the UK for centuries – and that Canadian troops have fought and died on the same battlefield as British soldiers (I do not support all imperialist war – but facts are facts! I have read Martin Knight’s book mentioned below. He carries-out very good research – and there is much of local historical value in the body of the narrative he constructs. A weakness (in my view) is that there is a more or less complete disconnect with the broader national and international situation that undoubtedly fed into this situation.

The broader perspective matters as the behaviour of those involved can (in-part) can be explained, or at least placed into a proper perspective. A Foreword to the book – Russia is simply described as “disintegrating” in 1919 – whilst the British Establishment is fearful of Bolshevism (a working-class uprising). What is not made clear is that Russian had lost around 5 million men fighting on the Eastern Front during WWI as an ally of Great Britain between 1914-1917. The 1917 Socialist Revolution ended the slaughter – whilst at least 14 countries joined Russia to form a “Revolutionary Front” (in late 1922 – this would transform into the Soviet Union). The UK presented this development not as a good thing for humanity – but rather a “betrayal” – with Russophobia prevalent throughout the Press and officialdom.

As a consequence, the UK despatched around 57,000 (reluctant) British troops to invade Russia, alongside the US, Canada and 11 other countries during early 1918. The Germans (and four of her allies) also invaded Revolutionary Russia (primarily West Ukraine – where Germany was joined by Catholic Ukrainians) between April-November, 1918 – but was forced to withdraw their troops with the defeat of Imperial Germany in France. A Laughable fact omitted on each Poppy Day – due to it embarrassing nature – is that between April-November 1918 – British and German troops fought on exactly the same side whilst WWI was still in effect. As matters transpired, the newly formed Red Army slowly gathered experience and momentum, and inflicted one defeat after another on the British (who committed a War Crime in Baku-Azerbaijan). Between 1918-1921, the collective West caused around 10.5 million casualties within Revolutionary Russia – the highest number of killed in any Civil War – with many modern historians treating this shocking statistic as the “Russians doing it to themselves”. By 1919, the war in Europe was over and the ordinary working-class British soldiers in Russia wanted out and to go home. Meanwhile, a wave of xenophobia spread throughout the UK as part of the celebrations of prevailing over the Germans in WWI.

This culminated with the British government rounding-up and deporting around 20,000 Chinese people in the Liverpool during 1919 (the Labour Party would carry-out a similar – but small scale purge – of the Chinese from East London in 1946) – many of whom had fought in France for the UK (in unarmed Labour Battalions on the frontline). Perhaps the local population of Epsom should shoulder some of the responsibility for the death of PC Green – as it was their initial violent action that targetted Canadian soldiers and which attracted a retaliation – all be it an excessive one (I do not condone the murder of PC Green – or any violence – against Canadians or British people). I suspect if Chinese people had rioted or beat a police officer to death – the reaction would have been far more severe than 5 months confined to barracks! My point is that things may not be as black and white – as portrayed in Martin Knight’s otherwise interesting book. ACW (28.2.2025)

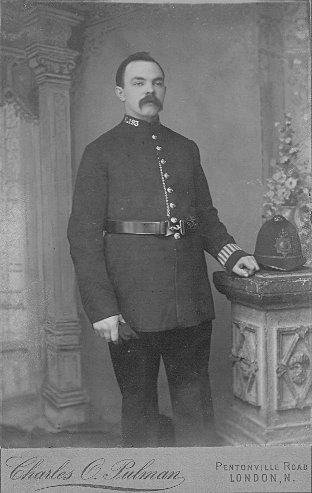

‘After a Canadian soldier was arrested and taken to Epsom Police Station a group of Canadian soldiers descended on the station demanding his release; initially they were dispersed but later returned and attempted to force their way in to the station. Sergeant Green led officers from behind the mob and attempted to disperse them. He was later found dead as the mob retreated.

Found dead with a serious head injury after defending Epsom Police Station against an attack from a group of Canadian soldiers. Earlier, after a Canadian soldier had been arrested and taken to the Police Station, a group of his compatriots descended on the station demanding his release. Initially they were dispersed but they later returned and attempted to force their way in to the station. Sergeant Green led officers from behind the mob and attempted to disperse them once again but as the mob retreated he was found fatally injured.’

Probably around 1995, I spent a weekend in Paris (via coach – ironically travelling on Epsom Tours – we boarded at about 6 am outside what was then the Main Post Office in Grove Road, Sutton – we lived a street or from this location). A retired, elderly Colonel (British Army) and his wife were seated behind us – and were fine examples of a gentleman and a gentlewomen. However, the seats were not that comfortable or particularly roomy (similar to an economy seat on the average cut-price airline). When I sat up to look at something (cannot remember what) – the back of my seat “rocked” dramatically forward and back in-front of the Colonel – who quite rightly advised me to “Be still young man!”

This is one of the best “adjustments” I have ever been subjected to (as he and his wife were very polite in their condescension – I was happy to offer an apology – which they accepted with good grace). He spoke with the natural authority his class and status had imported into him from birth (his wife appeared slightly “sorry” for me – as if I was being mothered – my actual mother would have beaten me with a coal-shovel). At the time, I was acting undercover – pretending I belonged amongst such people (I do not, by the way, but I occasionally have to pull it off).

But I digress. Me and my partner at the time (Cindy) travelled through the Channel Tunnel (via “LeShuttle” Folkstone to Calais – where our coach drove onto a train – whilst we remained sat on the coach throughout) with the coach disembarking and continuing to our destination. We stayed in a hotel the French Authorities had placed in the outskirts of Paris – next to a high-rise blocks of flats – what we would call a Council Estate in the UK (comprised of State-owned housing). Apparently, this was not an unusual arrangement, and was an attempt by various French governments to inject business, employment, and wealth into remote (and sometimes deprived) areas.

The logic is understandable – but many tourists arriving in these culturally bleak areas were shocked after paying so much money for their holiday. As my partner was ethically Chinese – and I look White – there was the occasional comment from the locals – including a mini-car full of skin-heads stopping on the main road to verbalise what we assumed to be racial abuse – before they were driven-off by other motorists. Although we were both trained martial artists – this was a dangerous situation – as we were out-numbered in a foreign land. Still, we survived our “all-inclusive” sojourn (although we were required to pay extra for a single breakfast we decided to enjoy together away from the main British group – as if we were trying to leave the hotel without paying at the end of our visit.

We were never advised this was a separate cost – although both the food and service was better than normal – I suppose we should have known via the clues) and learned the golden rule that tourists only leave the hotel in escorted groups – preferably in official transport. This is how we eventually got to Paris proper and enjoyed its rich an ancient history. We boated on the River Seine (under a bridge for lovers) – and had an odd experience in a café on the East Bank – where a group of French students stopped us leaving for a few minutes by standing in-front of the entrance. Someone said we were English (in French) and reluctantly we were allowed to leave (this was nothing to do with the bill this time as we had paid for cups of tepid tea at the counter). We also found an Indian Restaurant – which only served one single dish – Chicken Tikka Masala – as the French are not that keen on Indian food. I think each dish was around 30 francs – which was huge compared to UK prices!

On the way back on the coach, we traversed a route through the French and Belgium countryside – visiting a number of allied WWI monuments and war cemeteries. The coach then stopped for an hour at the Vimy Ridge War Memorial – a piece of French land won by Canadian troops from a stubborn Imperial German occupation during WWI (this particular Battle of Vimy Ridge occurred between the 9th-12th of April, 1917). Although British and French troops had tried to take this area before (suffering substantial losses) – none of these attacks had been successful. The area is as bleak today as it was then – preserved as an stretch of entrenchment with a Canadian flag flying above it. The old Colonel travelling with us exclaimed “Of course, the brave Canadians!”

To be honest, other than the fact that WWI was a bourgeois-inspired holocaust against the working-class (my paternal great grandfather – Archibald Wyles – fought in it, although not in the trenches) – I knew nothing about this place – although I am glad that I did see it with my own eyes and had the opportunity to walk about the trenches that so many workers died defending (and attacking) one another for pointless imperialist objectives. As matters transpired, the Canadian troops lost 3,598 dead and 7,004 wounded – whilst German casualties were not recorded. A great deal is made of the Canadian contingent given the task of taking the high-ground of Vimy Ridge (situated on the Arras Front) – but the truth is that thousands of French and British troops had previously been killed and wounded throughout the war – trying to take a slight “peak” from which a Staff Officer could conveniently spy on the enemy through a pair of field-glasses.

Whilst the Germans, British, US, Canada (a 4,200 contingent – see “From Victoria to Vladivostok” by Benjamin Isitt), and a host of other countries “invaded” Revolutionary Russia between 1918-1921 (a disgraceful incursion that killed 10.5 million Russians – but played-down in the history books – and now treateded as if it did not happen) – many thousands of Canadian troops who had served in France during WWI were billeted in the UK after the war for what appeared to be no reason at all. These troops wanted to go home – but were prevented from doing so – I suspect in-case they were required to be sent to Russia in a Western war of aggression that was not going well. The problem the Western Authorities had was that many of the working-class soldiers simply did not want to go to war with a “Socialist” country – as Bolshevik thinking was very popular amongst the workers at the time. Still, none of these observations are excuses for drunkardness, insubordination, and riot from professional soldiers on active service outside their home countries. Particularly when it culminates with the death of an unarmed Police Constable – who died doing his duty protecting the local populace. This is what my local newspaper recalled of this incident in a 2007 aticle (which I remember reading at the time – after the newspaper had fallen through my letter box in Westfield Road):

The riot of 1919: Assault on Epsom police station

2nd March 2007

On a balmy evening in 1919 an insistent knock sent Station Sergeant Thomas Green hurrying towards the front door of 92 Lower Court Road. The waiting messenger instantly delivered his news then disappeared into the dusk.

Frantically putting on his coat, starting for the exit, Sgt Green paused only to inform his daughter Lily that Canadian soldiers were about to overrun Epsom police station. He never returned home.

The mob violence that killed the father of two is regarded as the most brutal episode known in Epsom. Last month visitors to Bourne Hall Museum sat transfixed as they were told of its origins in the sporadic clashes involving Canadian soldiers stationed at Surrey camps during both wars.

Order was always quickly restored. Until the night of June 17. That night the Metropolitan Police was called to a disturbance at the Rifleman pub in East Street.

Lacking the luxury of a Ford Transit van, arresting officers conveyed two Canadian soldiers to the police station in Ashley Road. Over the half-mile journey they were trailed by servicemen clamouring for their compatriots’ release.

Taking up the story Jeremy Harte, a curator at the museum, says: “A number of police officers went into the road to disperse the assembled crowd who, deciding that discretion was the better part of valour, ran away through the adjacent Rosebery Park. Quiet being restored, it was now hoped the trouble was at an end.”

But the trouble hadn’t even begun. Soldiers returned to camp, Jeremy says, only to recruit hundreds of reinforcements and, arranged in a military formation and sounding bugles, they marched on the station.

Once there, they armed themselves by tearing slats from a wooden fence separating the building from private houses. Inspector Pawley instructed his men – three sergeants and seven constables – to form a line across the facade.

“He went to the gate and attempted to disperse them but was shouted down. The mob were not disposed to listen to reason,” Jeremy says.

“Their mood turned uglier and a barrage of bricks, stones and pieces of wood rained on the police line, and the mob surged toward the station.”

Deciding offence was the best form of defence, Insp Pawley, Sgt Green and others charged into the crowd, successfully clearing the garden. In the mêlée Sgt Green was felled by a blow to his head.

Unconscious, he was carried to a roadside house, where he lay until the tumult subsided with the prisoners’ eventual release. He died in an infirmary the next morning.

Remarkable scenes attended his funeral as rows of mourners lined the route from Lower Court Road to the Ashley Road Cemetery. Among the procession were 800 police officers and river police, 60 special constables, fire brigade members, council workers and patients from Horton War Hospital. At Sgt Green’s home so many flowers filled the front room that they spilled into the road.

Later Lord Rosebery presented the police officers who defended the station with gold medallions, on to which was inscribed, “as a token of public appreciation of the gallant fight by the Epsom Police 17th June, 1919”.

Insp Pawley was given a clock and his young son received a silver cigarette case from Sir Roland Blade MP. There was a £310 cheque (£13,410.37 in today’s money [2025] – but with a substantially greater buying power then – than now) for Mrs Green.

Lord Rosebery spoke of being deeply moved by the ceremony. “I wish with all my heart that I could express all that I feel on this occasion but I cannot.”

Was Epsom policeman’s death covered up by Government?

18th June 2009

To mark its 90th anniversary, local historian Brent Stevens reports on a riot started by Canadian soldiers that led to the death of a police officer in Epsom.

Yesterday, June 17 marked the 90th anniversary of a riot in Epsom by Canadian soldiers that resulted in the death of Police Sergeant Green.

His memorial can be seen today in Epsom cemetery. His epitaph reads: “In memory of Station Sergeant Green who found death in the path of duty.

“He was killed defending the Epsom Police Station against a riotous mob.”

What makes his death significant is that his murderer was never really brought to justice and that some in authority supported this for political reasons.

The “riotous mob” was in fact more than 400 soldiers on the rampage and the words “found death” on his gravestone were used rather than murdered.

Why was this? It was 10 years later that Sergeant Green’s murderer, when arrested in Canada on another offence, admitted his guilt.

By then Scotland Yard was not really interested and a prosecution was never considered. What caused this apparently callous action and why was justice not pursued as vigourously as we might have expected?

Throughout the Great War, many troops from the British Empire had fought with distinction. Canada produced about 600,000 men from 1914-18, taking 210,000 casualties, with over 56,000 dead.

They were awarded 63 Vicoria Crosses. The awesome Vimy Ridge memorial in northern France bears testimony to their bravery and loyalty during that dreadful period.

However, when war ended in November 1918, many troops, easpecially those from overseas, expected to be de-mobbed and repatriated as quickly as possible. Unfortuanely this did not happen.

In fact de-mobilisation plans had been in the Government’s thoughts since 1917.

War Secretary Lord Derby thought that in order to help the country’s economy, the most skilled workers should be released first into the key industries.

However these were the very workers who had been the last to be conscripted and the unfairness of this caused small scale mutinies within the British Army in Calais, Folkstone and London.

This inequitable system was changed by the new Minister of War – a certain Winston Churchill – in January 1919.

He decided men should be de-mobbed on the basis of age, length of service and number of wounds received. This in effect was a “first in- first out” policy.

This worked well for British troops, but Dominion troops were left hanging around for months. In March 1919 disgruntled Canadian troops rioted in Rhyl and this was repressed only after a number of men had been killed.

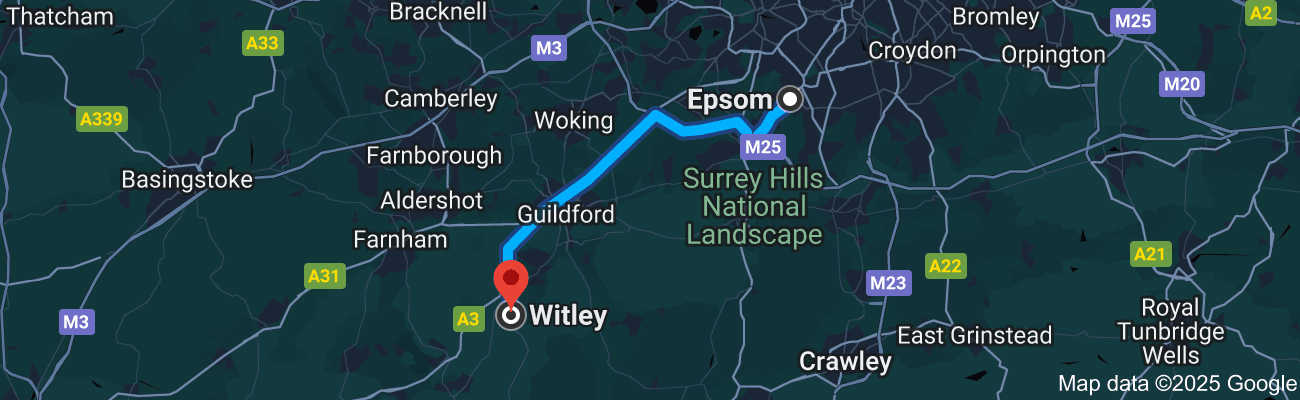

Australian troops in Liverpool and Cardiff created similar disturbances and on June 13, 1919, Canadian troops again rioted in Witley, commiting arson along the way.

So it was against this background that the riots in Epsom four days later should be viewed.

Feelings about the length of time it was taking to send them home rankled within the minds of Dominion troops who saw Britain slowly returning to normality by the summer of 1919.

In that year Ascot took place with renewed splendour, as did the trooping of the colour and the Derby, which was actually on June 17, with people determined to celebrate the ending of the war.

An intoxicating mixture of joy, alcohol and families enjoying a day out, must have created an atmosphere of anguish at the Canadian camp at Woodcote Park, where sick and wounded men were staying, longing to be shipped back home.

After seven months of waiting, their patience finally snapped later that evening.

At 9.15pm police were called to the Rifleman pub in Epsom because a fight had broken out between a Private MacDonald and a sergeant, both in the Canadian Army.

The police only arrested MacDonald and when his friend, Private Veinotte, came to help him, he was arrested too.

To take them both to the police tation, they had to walk along Epsom High Street – in full view of the many other Canadians in the town.

Twenty of them immediately gathered outside the police station in Ashley Road, demanding the release of the two men.

They were soon dispersed and returned to the Woodcote Camp.

Here, discontent spiralled out of control, and despite pleas from their officers, in particular Major Ross, some 400 men set off back to the police station.

The police, anticipating trouble, asked the Canadians to take the two men back to the camp, but the CO thought that was unsafe and asked the police to keep them at the station. The scene was now set for the appalling tragedy.

On their way to Ashley Road, rioting Canadians broke windows at the Ladas pub and commited other acts of vandalism.

This slowed them down and allowed Major Ross to get to the police station first. Inspector Pawley (in charge of Epsom police station) prepared to defend the station, with 22 men at his disposal.

Requests were made to summon help from surrounding stations and reinforcements were sent, but by bike they would arrive too late to help. Pawley was keen to hand over the prisoners to Ross, but the mob had already arrived at the front door.

Ross tried to calm them down, but in the meantime some of the Canadians had broken into the station around the back and managed to release one of the prisoners.

Pawley organised a charge to clear everyone out of the station and succeeded in doing so. Encouraged, Pawley and Sergeant Green decided to charge them again and clear the Canadians from the back passage too.

Again this was effective, but in the ensuing melee Sergeant Green sustained a head injury. He was taken to Epsom Hospital, but died early next morning.

This tragic event was compounded by what happened two months later.

In August, 1919, Edward Prince of Wales, was due to tour Canada by way of thanking this Dominion for all their help during the last four years of conflict.

It is thought a large scale trial and prosecution of segments of the Canadian army might be counter-productive to the Prince’s efforts.

How much pressure was applied to the police to scale down their detective operation is difficult to prove, but it would seem that those in authority wished to take the heat out of the situation.

This might help to explain what happened next.

Police went to Woodcote Camp the following day to look for men with unexplained bruises and bloodstains.

PC Rose managed to identify two men and Insp Ferrer eventually arrested five soldiers.

However, little attempt was made to find the murder weapon and fingerprint it (probably an iron bar ripped out of one of the cell doors).

Some Canadians pinpointed Allan McMaster as the culprit.

He was a blacksmith by trade and would have probably been strong enouhg to rip out the iron raillings – but this was never really followed up with any determination.

At the trial the incident was portrayed as a good natured brawl that got out of hand and the men were charged with manslaughter, not murder.

Even this charge was changed by the jury to “rioting” and the men served five months in prison before being discharged.

In sentencing the five Canadians, the judge was asked to take their war record into account. This might be significant for some, but two of the prisoners had never been to France; one had but had seen no action.

Allan MacMaster, who owned up to the murder a decade later was in the camp because of illness caused by a STD – not a war wound The funeral of Sergeant Green was a massive affair and the fact the culprit never really had to pay for his crime must have angered many people.

There can be no doubt of Canada’s courageous effort in the Allied war effort, but this episode is one they would probably want to forget.

It is suspected there were some in high government who preferred to bury this incident rather than see justice done.

similar disturbances and on June 13, 1919, Canadian troops again rioted in Witley, commiting arson along the way.

So it was against this background that the riots in Epsom four days later should be viewed.

Feelings about the length of time it was taking to send them home rankled within the minds of Dominion troops who saw Britain slowly returning to normality by the summer of 1919.

In that year Ascot took place with re-newed splendour, as did the trooping of the colour and the Derby, which was actually on June 17, with people determined to celebrate the ending of the war.

An intoxicating mixture of joy, alcohol and families enjoying a day out, must have created an atmosphere of anguish at the Canadian camp at Woodcote Park, where sick and wounded men were staying, longing to be shipped back home.

After seven months of waiting, their patience finally snapped later that evening.

At 9.15pm police were called to the Rifleman pub in Epsom because a fight had broken out between a Private MacDonald and a sergeant, both in the Canadian Army.

The police only arrested MacDonald and when his friend, Private Veinotte, came to help him, he was arrested too.

To take them both to the police tation, they had to walk along Epsom High Street – in full view of the many other Canadians in the town.

Twenty of them immediately gathered outside the police station in Ashley Road, demanding the release of the two men. They were soon dispersed and returned to the Woodcote Camp.

Here, discontent spiralled out of control, and despite pleas from their officers, in particular Major Ross, some 400 men set off back to the police station.

The police, anticipating trouble, asked the Canadians to take the two men back to the camp, but the CO thought that was unsafe and asked the police to keep them at the station. The scene was now set for the appalling tragedy.

On their way to Ashley Road, rioting Canadians broke windows at the Ladas pub and commited other acts of vandalism.

This slowed them down and allowed Major Ross to get to the police station first. Inspector Pawley (in charge of Epsom police station) prepared to defend the station, with 22 men at his disposal.

Requests were made to summon help from surrounding stations and reinforcements were sent, but by bike they would arrive too late to help. Pawley was keen to hand over the prisoners to Ross, but the mob had already arrived at the front door.

Ross tried to calm them down, but in the meantime some of the Canadians had broken into the station around the back and managed to release one of the prisoners.

Pawley organised a charge to clear everyone out of the station and succeeded in doing so. Encouraged, Pawley and Sergeant Green decided to charge them again and clear the Canadians from the back passage too.

Again this was effective, but in the ensuing melee Sergeant Green sustained a head injury. He was taken to Epsom Hospital, but died early next morning.

This tragic event was compounded by what happened two months later.

In August, 1919, Edward Prince of Wales, was due to tour Canada by way of thanking this Dominion for all their help during the last four years of conflict.

It is thought a large scale trial and prosecution of segments of the Canadian army might be counter-productive to the Prince’s efforts.

How much pressure was applied to the police to scale down their detective operation is difficult to prove, but it would seem that those in authority wished to take the heat out of the situation.

This might help to explain what happened next.

Police went to Woodcote Camp the following day to look for men with unexplained bruises and bloodstains.

PC Rose managed to identify two men and Insp Ferrer eventually arrested five soldiers.

However, little attempt was made to find the murder weapon and fingerprint it (probably an iron bar ripped out of one of the cell doors).

Some Canadians pinpointed Allan McMaster as the culprit.

He was a blacksmith by trade and would have probably been strong enouhg to rip out the iron raillings – but this was never really followed up with any determination.

At the trial the incident was portrayed as a good natured brawl that got out of hand and the men were charged with manslaughter, not murder.

Even this charge was changed by the jury to “rioting” and the men served five months in prison before being discharged.

In sentencing the five Canadians, the judge was asked to take their war record into account. This might be significant for some, but two of the prisoners had never been to France; one had seen no action at all.

Allan MacMaster, who owned up to the murder a decade later was in the camp because of illness caused by an STD – not a war wound.

The funeral of Sergeant Green was a massive affair and the fact the culprit never really had to pay for his crime must have angered many people.

There can be no doubt of Canada’s courageous effort in the Allied war effort, but this episode is one they would probably want to forget.

It is suspected there were some in high government who preferred to bury this incident rather than see justice done.

Epsom Riot of 1919 investigated by local author in new book

2nd September 2010

An author who investigated the Epsom Riot of 1919 lifts the lid on the events surrounding the death of a police officer in his new book.

In his book – We Are Not Manslaughterers (The Epsom Riot and The Murder of Station Sgt Green) – Martin Knight takes a look at the build-up of the riot and at the real reason behind the unrest between locals and Canadian soldiers, which culminated with the death of Sergeant Thomas Green.

His research into the episode points out that there was something a bit more sinister in the background, rather than it being just a drunken brawl that ignited the flame and drove more than 400 Canadian soldiers to try and overrun Epsom Police Station.

Mr Knight claims Sergeant Green’s death was a major crime. A policeman being killed on duty had never happened in this country before and Mr Knight believes it would have been worthy of extensive media coverage.

In the book, he claims it was “brushed under the carpet” by the powers that be.

Mr Knight, who lives in Ewell Village, said: “When I finished writing my last book I was looking at what to do with the next one and the idea came to research this episode, which is one of the biggest things that ever happened in Epsom, but it’s really not that well-known elsewhere in the country and I was hoping to find out why.

“This always struck me as really weird. He was the only policeman that got killed in his own police station in this country.

“The confessed murderer, Allan MacMaster, carried much guilt, confessing in 1919 as already known, but I also found out he eventually committed suicide.

“He also became a hero back in Canada after bravely saving the lives of colleagues in a mining disaster.”

The mob violence that killed the father-of-two is regarded as the most brutal episode known in Epsom. Mr Knight’s book, out today (September 2), reveals half of the soldiers that stood trial for the riot were suffering from an STD among and it was well-known Epsom women had relationships with the Canadian soldiers at the time.

He said: “It follows that some would have become infected and this explains the extraordinary hostility the Epsom men had towards the Canadians and why there was fighting every night on the streets of Epsom in the summer of 1919.”

Mr Knight also uncovered proof that there was a dialogue between King George V and the Canadian authorities over the soldiers that were imprisoned, making it likely that an informal Royal Pardon was arranged to coincide with a Prince of Wales tour of Canada.

We Are Not Manslaughterers, published by Tonto books, features never before seen pictures of Sgt Green and Mr MacMaster.

Martin Knight is the author of Battersea Girl, Common People and George Best’s final autobiography.