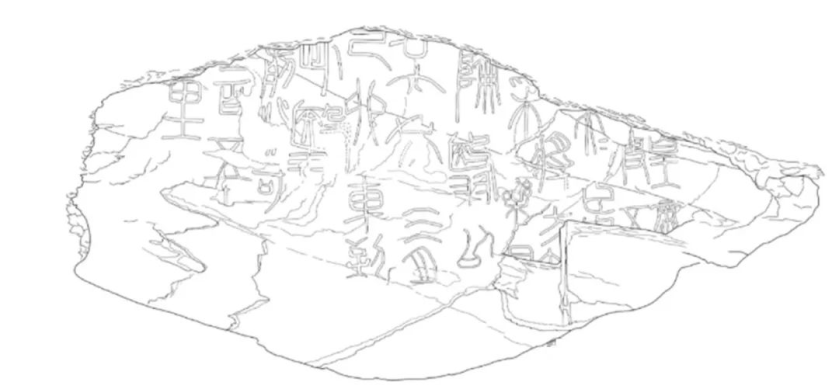

Translator’s Note: I am not happy with the English-language translations that are floating around and so I have re-translated this vitally important text. There are 37 Qin Seal characters on the stone engraving (which includes 31 distinct ideograms and six small boxes [“□”] which represent missing or unrecognizable words) – not counting the end of line markers of “/”. One ideogram is described as being “合文” (Hewen) – or the product of “combined writing”. This is a process which sees two distinct ideograms neatly amalgamated into one compact ideogram – that then occupies a single square space. There are 12 vertical columns – with the text written top to bottom – right to left (the intended direction of reading). The Qin Dynasty Script reads as follows (as it appears on the stone:

| 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 里 | □ | 前 | 此 | 己 | 卅 | 陯 | 采 | 將 | 大 | 使 | 皇 |

| 百 | □ | 翳 | 卯 | 七 | 翳 | 樂 | 方 | 夫 | 五 | 帝 | |

| 五 | 可 | □ | 車 | 年 | 以 | □ | □ | 臣 | |||

| 十 | 到 | 三 | □ | ||||||||

| 月 | |||||||||||

31 = Ideograms 6 = Spaces (□) 11 = Column End (/)

The original Inscription (in modern left to right – horizontal script) reads:

“皇帝/使五/大夫臣□/將方□/采樂□/陯翳以/卅七年三月/己卯車到/此翳□/前□可/□百五十/里”。

My new translation reads:

‘Emperor Qin commanded five ministers-officials to gather medicinal herbs on the Kunlun Mountain. The chariot approached Kunlun as ordered (arriving in the Zhaling Lake area) during the 3rd month of the 26th year*. The group had travelled 150 li (about 39 miles) when completing their journey.’

The Qin Emperor of a unified China was in fact King Ying Zheng (嬴政) (259-210 BCE) – the King of the State of Qin (situated in northwest China – now Shaanxi province). He was crowned the King of the State of Qin in 247 BCE. He became the Emperor of a unified China in 221 BCE – the presumed date of this inscription – which counts his rule as being in its “26th year” since his crowning as the King of the State of Qin [247 BCE] (rather than the 1st year as the Qin Empire [221 BCE]). There is an ongoing debate within China’s academic community as to whether the inscription is a) authentic, and b) the above interpretation is correct (the text appears to say “37” – some think this is a weathered inscription that should read “26”*. I have followed with the “26” narrative as this equals 221 BCE – whereas “37” would equal 209 BCE. As the Emperor Qin died in 210 BCE – this latter dating would not make sense. Furthermore, line 8 states the branch and stem year is “己卯” [Ji Mao] – which implies the year in question is “221 BCE”). A local Tibetan herdsman said he knew about the inscription as early as 1986 – and all his older relatives said it had always been present. Research is ongoing – but a recent and leading Xinhua article states:

‘The appearance of a carved stone engraved with the characters of the Qin Dynasty in the hinterland of the plateau will inevitably cause controversy within academic circles – but how to determine that it is not an imitation of later generations? How do we replace “expert empirical judgement” with solid “scientific evidence”? An expert team used a set of “all-inclusive” scientific and technological means to establish an “ironclad proof” for the authenticity of the Garitang Qin Engraved Stone. Using “high-precision information enhancement technology”, on the engraved stone text can be seen the obvious effects of ancient chiselling traces made by using traditional flat tools. This is in line with the characteristics of the times of the Qin Dynasty. Mineral and metal elemental analysis excludes the possibility of chiselling with modern (alloy) tools. Inside each notch and across the surface of the engraved stone – there is evidence of exposed secondary minerals, which have undergone long-term weathering. These findings exclude the possibility of a new engraving deriving from later – or contemporary times.’

From a political perspective, such a marker of Qin Dynasty sovereignty would suggest that the areas of Qinghai (Tibet) were incorporated into Chinese-controlled lands over a thousands before previously thought. ACW (15.9.2025)

Source: Xinhua Editor: huaxia 2025-09-15

XINING, Sept. 15 (Xinhua) — China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration announced on Monday that an engraved stone, discovered on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, is the only known Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.-207 B.C.) engraved stone still preserved at its original site and the one located at the highest altitude during the historic period.

The stone is situated on the northern shore of Gyaring Lake in Maduo County, northwest China’s Qinghai Province, at an altitude of about 4,300 metres.

The finding holds significant historical, artistic and scientific value, according to the administration. Emperor Qinshihuang of the Qin Dynasty unified China for the first time.

Chinese Language Text:

重要发现!扎陵湖秦代刻石得到认定!每经独家采访当地牧民:40年前就曾看见,在他家牧场内

每日经济新闻

2025-09-15

据央视新闻,刻石位于青海省果洛藏族自治州玛多县扎陵湖乡卓让村,地处扎陵湖北岸尕日塘坡地2号陡坎左下方,距湖岸约200米,海拔4306米。文字刻凿壁面总长82厘米,最宽处33厘米,刻字区面积约0.16平方米,距地面约19厘米。全文共12行36字,外加合文1字,共37字,文字风格属秦篆,保存较完整的文字信息为“皇帝/使五/大夫臣□/將方□/采樂□/陯翳以/卅七年三月/己卯車到/此翳□/前□可/□百五十/里”。

经高精度信息增强技术,刻石文字可见明显凿刻痕迹,采用平口工具刻制,符合时代特征。经矿物和元素分析,排除利用现代合金工具凿刻的可能。刻痕内部和刻石表面均含有风化次生矿物,经历了长期风化作用,排除了近期新刻可能。

鉴于尕日塘秦刻石的重要价值,国家文物局指导青海省文物行政部门,已将刻石核定公布为县级文物保护单位,划定了保护范围和建设控制地带,视同全国重点文物保护单位进行保护管理。并将在第九批全国重点文物保护单位申报遴选中予以重点关注。

6月8日,中国社会科学院考古研究员仝涛称发现秦始皇遣使“采药昆仑”石刻,引发考古界内外关于石刻的真伪大论辩。

另据每日经济新闻7月初报道,记者独家获悉,当地牧民多杰南杰称大约40年前已见该石刻,就在他家牧场内。7月7日,记者采访了多杰南杰。

“我最早看到石刻,大约是在1986年的某一天,但当时并不知道上面书写的是文字。”多杰南杰认为,在他之前应该也有人见到过石刻。

在后面放牧的20多年里,多杰南杰经过石刻所在地时,还会去瞧上几眼,所以,当今年6月“昆仑石刻”引发广泛关注,照片在网络上频频流传后,多杰南杰立刻认了出来,这正是那些年自己见过的那块石头。

三大谜团待解

玛多县石刻是否是“秦始皇遣使采药”遗迹,最终的定性仍需要国家权威部门来鉴定。而业内外围绕该石刻的疑惑大致聚焦在以下三大谜团,亟待破解。

谜团一:37字石刻有何玄机

持续引发公众关注的“昆仑石刻”,就静卧在扎陵湖畔北岸、距湖边约1公里一处凸出沉积岩上。

每经记者了解到,石刻上只有短短37字,内容大意为:

秦始皇廿六年,皇帝派遣五大夫翳率领一些方士,乘车前往昆仑山采摘长生不老药。他们于该年三月己卯日到达此地(黄河源头的扎陵湖畔),再前行约一百五十里(到达此行的终点)。

在当地人眼中,并不“新鲜”的石刻竟于今年6月多次上热搜,方寸间却成为学术界争议的风暴眼。

“昆仑”,在中国古代历史地理上占有很重要的地位,关于它的传说和神话很多。文化语境中,“昆仑山”常作为中华文明源头的象征之一,但其具体位置在哪里,是千百年来一直困扰学界的谜题,而非对应现在自然地理概念上的“昆仑山脉”。若“昆仑石刻”真为秦代遗迹,就已透露了“昆仑”地理位置的玄机。

但围绕这块石刻是否是“秦始皇遣使采药”遗迹的争议,至今仍未平息。

谜团二:始皇“廿六”年还是“卅七”年?

6月8日,仝涛提出刻文是“廿六年”(即秦始皇二十六年,公元前221年)。此纪年与《史记》记载的秦始皇活动轨迹存在矛盾——公元前221年秦刚统一六国,秦始皇尚未大规模派遣方士求仙,且“采药昆仑”的人应该是前一年就出发了,其行为缺乏历史背景支撑,引发广泛质疑。

目前多位学者倾向将刻文中的纪年释读为“卅七”年。刘钊在6月30日的文中表示,“廿六”是“卅七”的误摹,并将昆仑刻石中的“卅”和“七”字与里耶秦简“卅”和“七”字进行对比。

但7月2日,仝涛在《中国社会科学报》中回应该问题时称,“倾向于识读为‘廿六’。不过,关于该年号信息的论证还需要再结合刻石的超高清图像进一步确定。”

谜团三:字迹是否符合自然风化规律

以北京语言大学教授刘宗迪为代表的质疑者认为,该石刻在高海拔高寒区域,经历两千多年应当风化严重,而如今字迹仍较为清晰,显然不符合自然风化规律。还有声音更进一步怀疑其为现代电钻工具所刻,刻文疑似人为“避让”了岩石原有的裂缝。

对此,支持者则强调石材材质及气候因素。仝涛最初在文章中初判石刻材质为玄武岩。玄武岩硬度高、抗风化能力强。《甘孜岩画》专家组成员周行康近十年实地调查了180多处青藏高原史前岩画,他以降水量和气候相近的昆仑山脉岩画、玉树岩画、甘孜北路岩画,以及海拔相近、降水量稍小的阿里日土岩画等为证,认为“昆仑石刻”符合距今两千年以上的观察经验。

河北师范大学特聘教授汤惠生认为,降雨量和石质是影响石刻摩崖腐蚀程度的两大重要因素。他强调,虽然石刻刻痕腐蚀程度尚浅,但其石锈(又称岩晒、氧化层或沙漠漆)的色泽颇深,几乎与岩石原始面一致,由此可以确定其古老性。

兰州大学资源环境学院教授王乃昂则认为,该地区地层为砂岩,抗风化能力远低于玄武岩。他指出,抗风化能力较强的秦泰山刻石、峄山刻石均已严重风化,但“昆仑石刻”风化却较轻,主要信息保存完好,成为一大疑点。

“据岩画研究专家讲,连上万年的岩画看上去都很新,尤其经雨冲刷后会显得更‘新’。既然上万年的岩画看去都很‘新’,两千多年前的石刻看上去‘新’有什么奇怪的呢?”刘钊指出。

如果多杰南杰40年前就看见过这块石刻,那“昆仑石刻”谜底到底是什么?是哪个时代,哪些先人鬼斧神工在海拔4000多米的寒冷之地凿下了这段文字,让后来者绞尽脑汁。争议仍然会持续,答案或将继续沉睡在高原冻土之中……

每日经济新闻综合央视新闻、每日经济新闻

每日经济新闻