Author’s Note: As my maternal grandmother was from Eire, and given she taught me about how some of my Kilmurray ancestors fought for the Confederacy – I have been researching this interesting history – particularly from the Irish perspective. I do not subscribe to the anti-intellectual viewpoint that stupidly suggests “Confederacy = Evil” – or some similar correlation. Neither do I believe the Confederacy was fighting for slavery – all this has been contrived by the winners – the current fascist government of which is generating havoc the world over. Whatever the case, a careful and thorough assessment of this history will grant a clear and balanced view. To this end I have accessed three books and combined their collective knowledge to describe a battle that lasted throughout the daylight hours of July 2nd, 1863 at Gettysburg (the second day of the three-day battle):

The Flags of the Confederate Armies – Returned to the Men Who Bore Them By the United States Government (1905) – United Confederate Veterans (Forgotten Books Re-Print 2018)

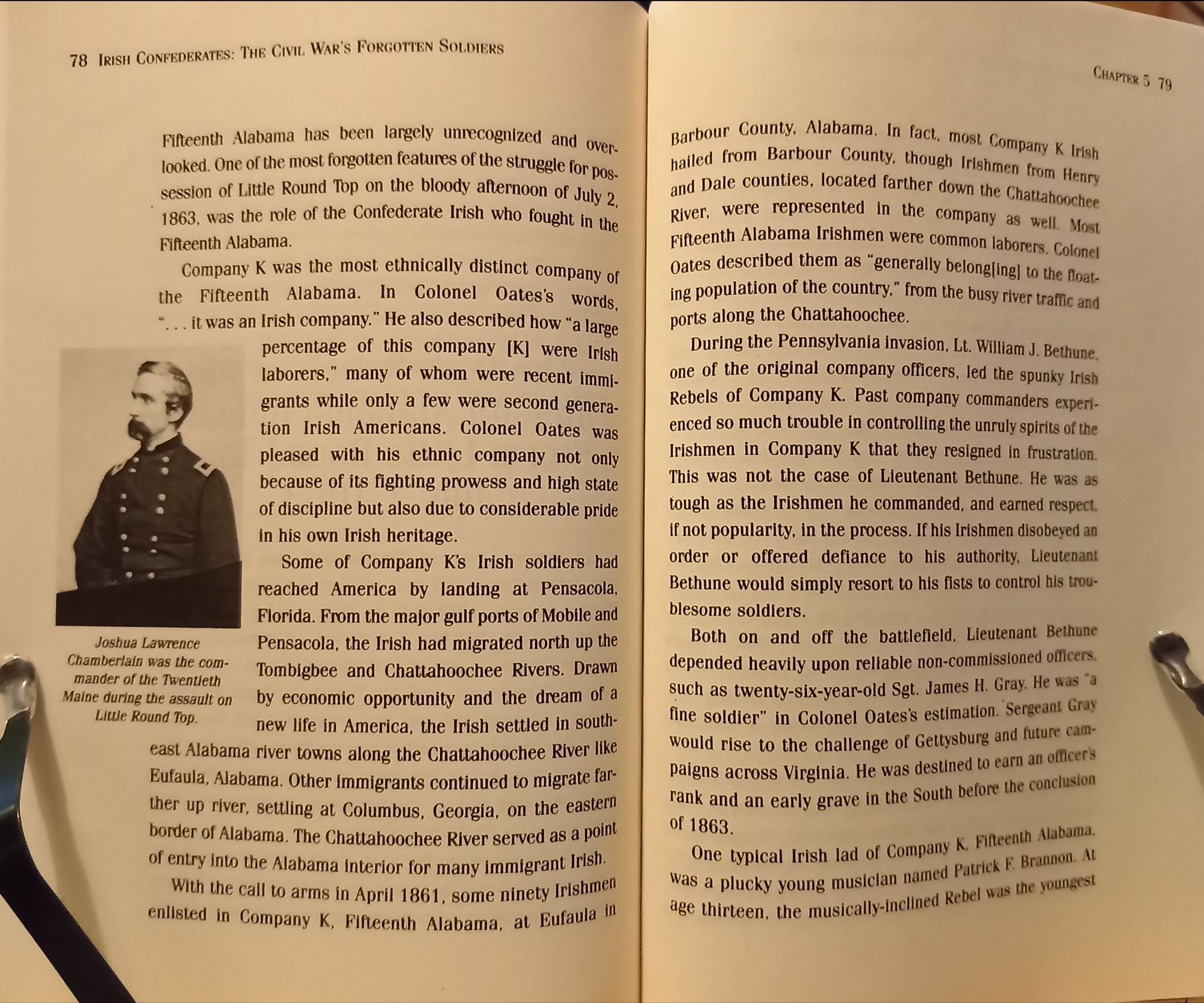

Phillip Thomas Tucker, Irish Confederates – The Civil War’s Forgotten Soldiers, Library of Congress, (2006)

Stephen W Sears, Gettysburg, (Mariner Books), 2004, Chapter 10

The weather was hot – and the Confederates had to advance over open ground before storming an inclined slope (in the form of a steep hill) – with the intention of sweeping the Federals off its top and consolidating the victory. The previous day had seen the Confederates sweep the Federals out of West and Central Gettysburg – and into the hills to its East. Washington was just 80 miles to the South – and legend has it that Lincoln was packing his belongings to flee! I have audio-typed part of a chapter from Stephen Sears’ book – carefully reproducing the text from an Audible edition (in my native British English). This provides a general background to the battle – but does not mention the Irish specifically – other than one or two fighting for the Union. For the story of “Company K” of the 15th Alabama Regiment of the Confederate States of America (CSA) – we must turn to the excellent work of Phillip Thomas Tucker – who has produced an excellent book examining the contribution to the Confederate cause made by the Irish! I am proud of these Irishmen who attacked up this hill for the freedom they sought! ACW (3.4.2025)

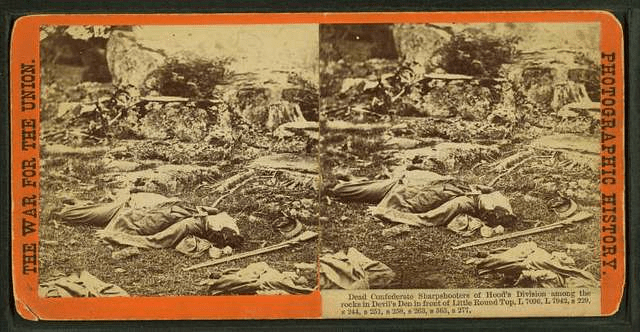

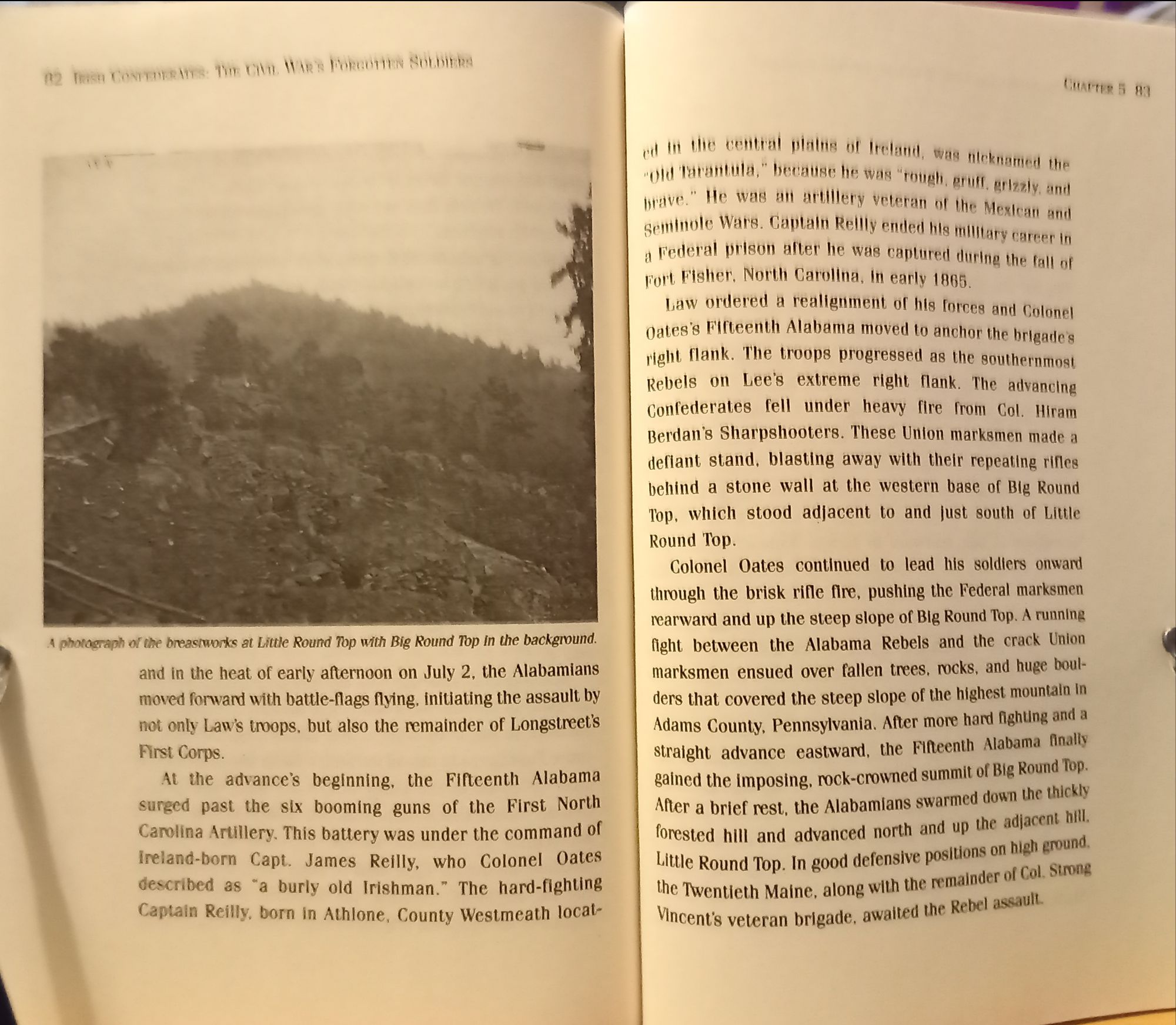

‘Meanwhile, to the furthest right, considerably delayed by their climb over the crest of Round-Top, would come two more of Law’s Regiments – the 15th and 47th Alabama. These were under the control of Colonel Oates (15th Alabama) – and Oates would make his fight independently of everyone else. Private Elijah Cone of the 29th Maine described the battleground, “Our Regiment was formed in an open-level space, comparatively free from rocks and bushes. But in our front was was a slight descent, fringed by ledges of rock. Beyond this line of ledge and other rocks – the eye could not penetrate on account of the dense foilage of bushes.” In their opening assault, the Texans and Alabamians emerged from this cover to strike at the Federal centre – the 44th New York – then slid progressively right against the 83rd Pensylnania and the 20th Maine. “It did not seem to me that it was very severe at first,” Colonel Chamberlain recalled, “The fire was hot, but we gave them as good as they sent, and the Rebels did not so much attempt at that period of the fight to force our line as to cut us up by their fire.” As Private Cone remembered it, “Soon, scattering musketry was heard in our front – then the bullets began to flick twigs and cut the branches over our heads – and leaves started to fall actively at our feet. Every moment the bullets struck lower and lower, until they began to take effect in our ranks. Then our line burst into flames, and the crash of musketry became constant.” The 4th Texas made its first attack enspirited by the Rebel Yell – but after they were driven-back, the Texans did not waste their breath in further yelling. There was little co-ordination in this – or subsequent advances. At one-point, the 5th Texas – in the centre – found itself out front all alone, whilst its neighbouring Regimehts fell-back under their own orders. After two raggedly conducted assaults were repelled – the attackers proceeded more slowly and carefully, using the cover of rocks and trees, stressing marksmanship. “Casualties grew heavy on both sides – every tree, rock, and stump that gave any protection from the rain of mini-balls that were poured-down upon us from the crest above – was soon appropriated,” wrote Texan Val Giles, “John Griffith and myself pre-empted a moss-covered old boulder – the size of a 500ibs cotton-bail!” Colonel Oates’ two Regiments now joined the fight – focusing on the Union left manned by the 20th Maine. His opening assault was met, Oates remembered, “by the most destructive fire I ever saw!” His line waivered like a man trying to walk against a strong wind. In Colonel Chamberlain’s phrasing “They pushed up to within a dozen yards of us – before the terrible effectiveness of our fire compelled them to break and take shelter.” Using his 15th Alabama primarily, Oates now began to work around to the West – passed the Federal’s far-flank. To counter this threat, Chamberlain stretched and thinned his line – until it was only a single rank deep – and refused his left at a sharp angle. At the same time, the Texans at the other end of the battle-line pressed-hard against Colonel Vincent’s right-flank Regiment – the 16th Michigan. In isolation from the rest of the battlefield, the fight for Little Round-Top settled into a bitter, grinding battle of attrition among the rocks, ledges, and trees, with both flanks of the Yankee-line coming under growing pressure…

(The chapter continues to explain the many battles unfolding elsewhere in the region in some considerable detail. Union forces converge throughout the theatre of East Gettysburg – shoring-up the Federal-line and eventually causing the dominant Confeerate Army to withdraw – undefeated but certainly checked. What follows is the culmination of the battle on Little Round-Top relevant to the extract quoted above).

At the same time John Caldwell’s counter-attack was sweeping the Confederates out of the Wheatfield – and through Rose’s Woods – some three-quarters of a mile to the East, the bitter struggle for Little Round-Top was reaching its own traumatic finality. Both contestants here, the four Regiments of Strong Vincent’s 5th Corps Brigade, and the 6th Texas and Alabama Regiments from from Law’s and Robinson’s Brigades (of Hood’s Division) – had fought to the verge of mutual exhaustion. Lacking unified command, the Confederate attacks had been raggedly executed – grinding-down the defenders, certainly – but failing so far to dislodge them. The failure of their frontal-attacks turned the Rebels toward the Yankee flanks – which began to appear vulnerable. On the Federal far-left – William Oates’ determined efforts to turn the 20th Maine had pushed the Mainer’s-line almost back on itself – Oates set about collecting his remaining strength for one, final effort. On the Federal far-right, meanwhile, the 4th Texas, joined now by the 48th Alabama, had discovered a soft-spot. Colonel Vincent’s right-hand Regiment – the 16th Michigan – was the smallest of the Brigade’s Regiments to begin with. And then, its two-largest companies were deployed as Skirmishers to tie the line to the defenders of Devil’s Den. This detachment, and the casualties suffered in the first Rebel-assault, left the 16th Michigan manning its hill-side perch with hardly 150-men. Now, as the Texans and Alabamians once again scrambled up the rocky slopes toward him – the 16th’s Lieutenant Colonel Norval Welsh became rattled, and took a mis-step. He later claimed that some higher authority, he thought General Sykes or Weed (although neither were then on the scene) – called on the Regiment to pull-back up the hill to a more defensible spot. And one of his lieutenants, by an entirely unwarranted assumption of authority, ordered the Colours back. Be that as it may, Welsh and his Colour Guard, and a goodly number of his men left the battle-line for safer ground to the rear. Oliver Norton, Brigade Bugler, subsequently found Colonel Welsh with his Regimental Colours and some 40 or 50 of his men, well-behind the lines. Strong Vinvent saw the 16th Michigan’s flag going back, and the right of his line crumbling, and he rushed over to try and rally the remaining defenders, and was almost immediately shot-down with a mortal wound. Seeing the Yankee Colours in retreat – the Rebels redoubled their efforts. Already that sfternoon, Little Round-Top had witnessed two miraculously timely arrivals in the persons of Gouverneur Warren and Strong Vincent. And now it witnessed a third – Paddy O’Rourke leading the 140th New York into the breech. Patrick H O’Rourke – West Point ’61 – had ranked number one in the academy’s first Civil War graduating class – and then marked “highly promising”. He took command of the new 140th New York in September 1862, and July 2nd would be its – and his – first serious action. Following General Warren’s Directive, he led his Regiment up the rocky east-slope of Little Round-Top – with all speed – and then traced the sounds of the fighting to the south-crest. Whilst his men hastily formed line-of-battle – he inspected the scene before him – and recognised the crisis building on the right. Returning to his troops, Paddy O’Rourke swing-off his horse and waved his sword and shouted, “Down this way, boys!” – and led the way to what remained of the 16th Michigan about to fall under the Rebel’s rush. “It was about this time,” wrote Sergeant James Campbell, “that Colonel O’Rourke, cheering-on his men, and acting as he always does, like a brave and good man – fell – pierced through the neck by a Rebel bullet.” His enraged men rushed passed their fallen Colonel, and into the vacated-line, meeting a storm of fire – and delivering a storm of fire of their own. As for Colonel O’Rourke’s killer, one of the first New Yorker’s to reach the battle-line wrote, “That was Johnny’s last shot, for a number of Companys – “A” and “G” – fired instantly!” It was said that this particular Johnny was hit by actual count – seventeen times. The 140th arrived at the last possible moment to seize and hold the endangered flank. As one of its men summed-up, “We soon got our positions when we opened on them. They soon fell-back – our boys being too much for them. But they did cuts us down dreadfully whilst we were advancing.” The 140th New York engaged some 450 men that afternoon, and in those brief moments a quarter of them were casualties. On the other side, the 4th Texas and 48th Alabama stumbled back down the stoney-slope for the final time that sfternoon, having lost a quarter of their men, and leaving at least the right of the Federal-lines secure. On the opposite flank, the Little Round-Top drama rushed toward another climax. Here, the 20th Maine – like the 140th New York – was undergoing its first real test of battle. Colonel Oates grimly prepared once last all-or-nothing assault, and Colonel Chamberlain grimly pondered his diminished numbers, and depleted ammunition. Oates’ own man-power was considerably diminished, the 47th Alabama on his left was demoralised by the failed attacks, and had lost its Commander – lying badly wounded between the lines. “And” wrote Oates, ‘the leaderless men broke – and in confusion retreated back down the mountain.” Oates would have to make his attack with just his own 15th Alabama. He strode along his line cryng “Forward men – to the ledge!” But in the smoke and the din of musketry – he could not be easily seen or heard. He would have to lead by example. “I passed through the column waving my sword – rushed forward to the ledge – and was promptly followed by my entire Command in splendid style!” From one of his fallen-men he paused to snatch-up a rifle and fire-off several shots of his own. The Alabamians managed to gain the ledge and there was a savage, often hand-to-hand struggle, as they tried to hold it. As Chamberlain remembered the scene, “The edge of conflict swayed to-and-froe, with wild whirlpools and eddies. At times I saw around me more of the enemy than my own men. Gaps opening, swallowing, closing again, with sharp convulsive of energy.” The 29th’s Company Officers held their waivering line together by gripping their swords in both hands and pressing the blades flat against the men’s backs. There was a desperate scramble for the 15th Alabama’s flag – and it was saved – said Oates, “only when Sergeant Pat O’Conner stove his bayonet in through the head of a Yankee – who fell dead.” At the peak of the action, Colonel Oates witnessed his brother – Lieutenant John Oates – fall mortally wounded. With clubbed muskets, and in many cases their last shots, “in the midst of this”, said Chamberlain, “our ammunition utterly failed.” The Mainers finally gained control of the ledge and forced Oates’ exhausted Alabamians back down the slope. As Oates tried to rally his scattered troops, he sent for support to his left, to what was now the next Confederate Regiment in-line – the 4th Alabama. His aide soon returned to say there was no sign of anyone on the left, except Yankees. At the same time tt was reported that musketry was coming at the Alabamians from the far-right. Colonel Oates could see no alternative now but to retreat. At his signal, he told his Officers “We would not try to retreat in order – but everyone should run in the direction from whence we came!” But before he could give the signal – the matter was wrenched out of his hands. Joshua Chamberlain also took a decision, when he, like William Oates, believed it to be inevitable. His men around him were displaying empty cartridge-boxes. His line, he thought, was thinned far beyond the point of holding-off another charge. At the foot of the slope, in-front of him, he saw the hostile line now rallying in the low shrubbery, for a new on-set. All Chamberlain could think to do now to meet his orders to hold the position at all costs – was to launch a charge of his own. To surprise and break-up the Rebels before they could form for another attack. Just then, Lieutenant Holman Melcher, commanding Company F at the centre of the line, came to Chamberlain with the plea to let him advance his Company to rescue some wounded comrades trapped between the lines. “Yes, Sir, in a moment!” said Chamberlain, “I am about to order a charge!” His order, “Fix bayonets!” ran swiftly along the line. Lieutenant Melcher returned to his Company and immediately let it forward – along with the Regimental Colours! With a shout – the right-half of the 20th Maine charged down the slope. The order to charge had not reached the left-wing before the right started forward. But Captain Ellis Spear commanding on the left, saw the Colours advancing and quickly seized the moment. “The left took-up the shout and moved forward”, Spear recalled. Every man eager not to be left behind – the whole line – flung itself down the slope, through the fire and smoke from the enemy. The effect was stunning. As explained by Private Elijah Cone of the 20th Colour Guard, “The Rebel front-line, amazed at the sudden movement, thinking we had been re-inforced, threw-down their arms and cried-out “Don’t fire – we surrender!” The rest fled in wild confusion. To meet the earlier flanking assaults, the left of Chamberlain’s line had been sharply refused – until it was facing more East than South. The Confederates here, abruptly confronted by a line of rushing Yankees, took the shortest route to safety, which was South – toward Round-Top. In its pursuit, then, Captain Spear’s left-wing executed a spectacular (entirely spontaneous) right-wheel that swept all before it. To complete the Confederate’s discomfort, Captain Walter Moral’s Company B (sent-out earlier by Chamberlain as a skirmish-line guard on the far-left), saw Rebels fleeing straight across its front and unleashed murderous fire. By the time Colonel Oates issued his retreat order – the retreat was in full-swing. When the signal was given – Oates admitted – “We ran like a heard of wild cattle!” The woods that covered the saddle between Little Round-Top and Round Top – now became a wild tumult of smoke and gun-fire and running men and falling men. Corporal William Livermore of the Yankee Colour Guard described the sight of not often seen spectacle of fleeing Confederate soldiers, “Some threw-down their arms and ran – many rose-up begging to be spared. We did not stop – but told them to go to the rear, and we went after the whipped and frightened Rebels, taking them by scores.” Colonel Chamberlain, right in the midst of this melee, came face-to-face with a defiant Rebel Lieutenant who levelled his pistol at him and pulled the trigger. Somehow, the shot went ride, and Chamberlain knocked the pistol away with his sword, and forced the man’s surrender. Finally, well up the slopes of Round Top – the Confederates turned and made a stand and held back their pursuers. Chamberlain ordered recall – as his triumphant Companies rejoined their Colours – they gave three cheers! The 20th Maine, especially its Colonel, had passed the test battle with those Colours flying! Chamberlain and Oates each lost about one-third of their numbers in this head-to-head struggle on the Potomac Army’s far-left flank. Chamberlain would claim the capture of 368 Rebels from various Regiments – but by Confederate account – the total of prosoners lost from the six Regiments engaged at Little Round-Top came to 218 – there was surely miscounting on both sides. As gallant and dramatic as were the exploits of the 20th Maine and its Commander on July 2nd, they by themselves, did not save Little Round-Top for the Union. Colonel Oates, whose own conduct, and that of his 15th Alabama, was easily as gallant as that of the Mainers, spoke truthfully when he later admitted, “Had I succeeded in capturing Little Round-Top, isolated as I was, I could not have held it ten-minutes.” Indeed, it was Strong Vincent’s entire Brigade that won Little Round-Top. A triumph ensured by the arrival of Charles Hazlette’s Battery, and Stephen Weed’s V Corps Brigade – spear-headed by the 140th New York. The Union’s Little Round-Top victory was drenched in blood. Vincent’s Brigade – and the 140th New York together – suffered 485 casualties, or just over 27% of those engaged. Command casualties included Colonel Armstrong Vincent mortally wounded, and Colonel Patrick O’Rourke of the 140th New York – killed. Even as the victory was sealed, there came to additional Command casualties – Brigadier General Stephen H Weed had hardly arrived on the hill with his Brigade – when a Confederate bullet felled him with a mortal wound. Weed was only recently transferred from the Artillary to an Infantry Command. And in extremis he called for his friend – Artillerist Charles Hazlett – as he bent close to hear Weed, Hazlett was shot in the head and fell across his friend’s body. Speechless and and insensible, Hazlett died within the hour. Stephen Weed was borne to the rear – where he aide tried to comfort him. “General, I hope that you are not badly hurt,” he said. Weed replied, “I’m as dead a man as Julius Caesar.” And so he was.’

Stephen W Sears, Gettysburg, Harper Audio, (2023), Chapter 10 – A Simile of Hell Broke Loose!