‘And now, cousin, I feel that this unholy war was forced on me, for I was opposed to it at the start, but now I am in favour of prosecuting it to the last extremity. For if we do not gain our independence, I cannot see anything else, but slavery starring me in the face. And rather than submit to this, I would rather die, and I want to die like my noble brother at Shiloh. I want to die battling for my liberty.’

Private Daniel Kelly – Maxin’s Company of Sappers & Miners 3.8.1863 – to Cousin

William Glen Robertson, River of Death – The Fall of Chattanooga, The Chickamauga Campaign Vol. I, Audible, (2019) Chapter 7 – Bragg Bides his Time: 30 July-14 August 1863 (this book also includes the presence of a number of German “Communists” in the Confederate Army who had fled Europe after the 1848 uprisings)

Many American Civil War historical narratives give the (false) impression that the Confederacy lost at Gettysburg in 1863 – staggered on with a futile resistance for two-more years – and then surrendered at Appomattox. Nothing could be further from the truth. Tens of thousands of men bravely fought, died and were wounded on both sides between 1863-1865 – with the Confederacy winning a number of notable victories after Gettysburg. Private Daniel Kelly quoted above, fought in the Confederate Army in the Western Theatre of the Confederacy – as opposed to the far more famous Eastern Theatre (where Gettysburg was situated). Furthermore, Black, Chinese and Native American men fought in the Confederate Army – but their presence is more or less “erased” from history because such a presence tends to lead to inconvenient and even embarrassing questions.

I am, of course, well aware of the socio-economic reality of the South, premised as it was on the agrarian model with African slave-labour carrying-out the bulk of the work. Sometimes, Irish indentured-labourers (paying-off the price of their ship-ticket from Ireland) worked side by side with the Black slaves in the fields – and these men also joined the Confederate Army. Race-mixing even occurred and the reason a number of Black people today carry an Irish surname. Of course, I am not suggesting that a temporary (often “voluntary”) state of indentured labour is in anyway comparable to (involuntary) institutional slavery. They are as different as chalk and cheese – but these inconvenient realities did exist.

Jefferson Davis (a descendent of Welsh migrants) did once pass the ludicrous “20 Negro Exemption Act” – perhaps to counter Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation” – which stated that anyone who owned 20 or more slaves were automatically “exempt” from military service. As only around 2% of Southerners were rich enough to own slaves, and given that most of these men were elderly, rich and well-connected, very few (if any) would have been beneficially effected by this law. What this law did do was send a wave of discontent amongst the ordinary working-class men of the Confederacy who either owned no slaves, or perhaps had one or two servants. There was no way for them to escape the conscription the CSA had utilised. A little-known fact is that Northern States also owned slaves (Lincoln “exempted” these States from his “Proclamation”) and that many Northern businessmen owned shares in Southern plantations – taking a cut in the yearly profits attained through slave labour.

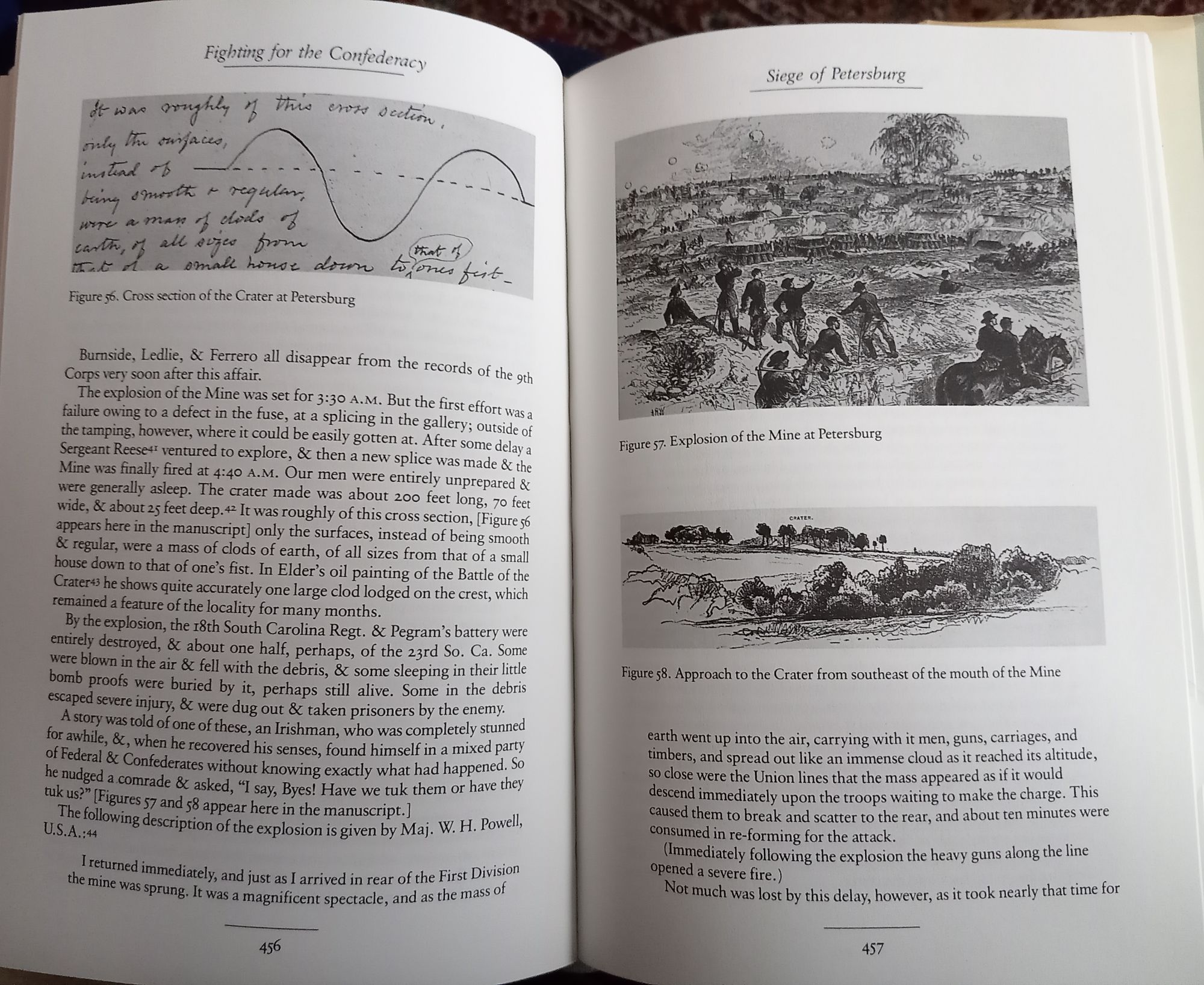

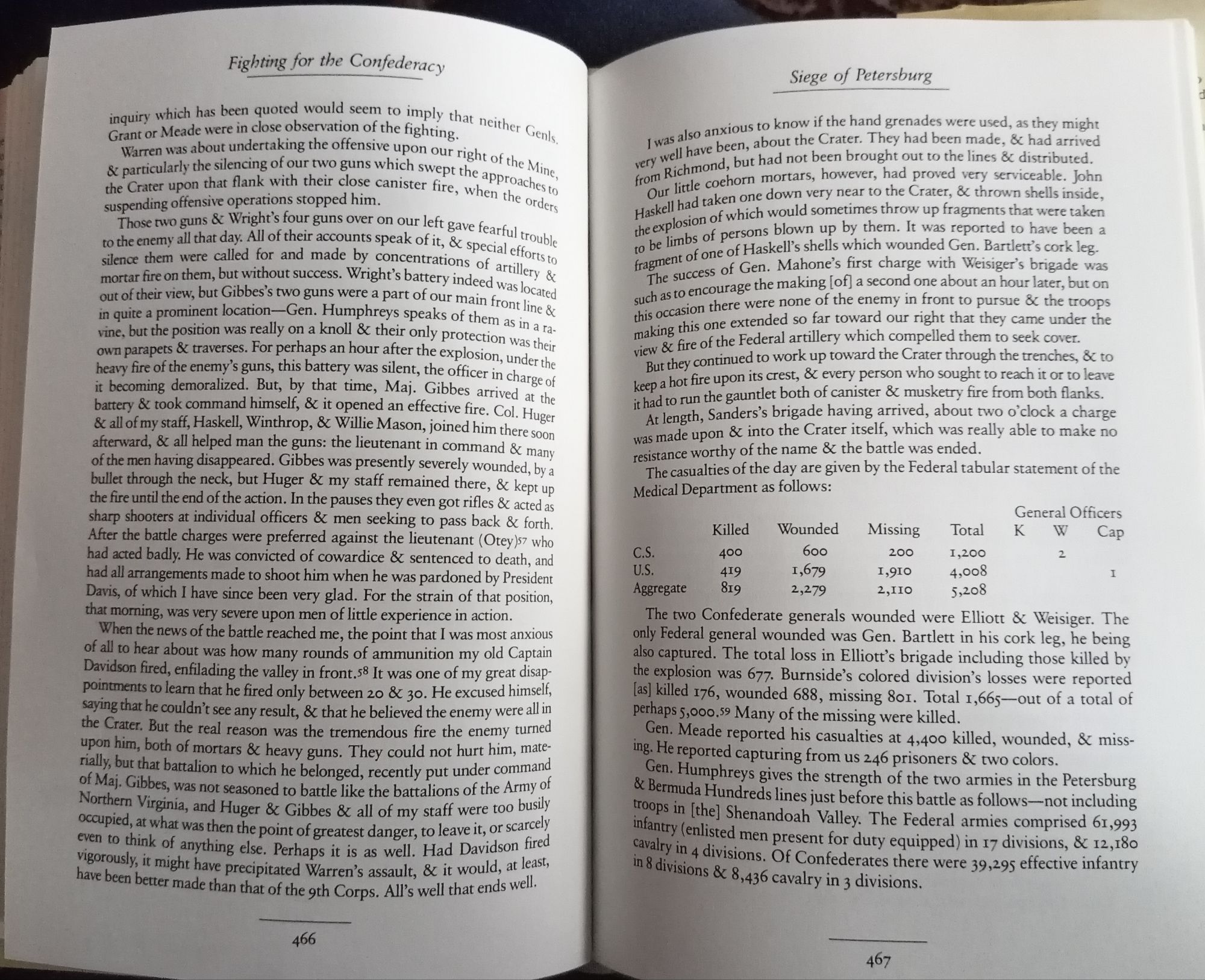

On the other hand, Jefferson Davis implied that if the Native Americans ceased all hostilities to the West – the Confederacy would “halt” all “White” migration into the West. This led to very good relations between the Confederacy and the Indian Tribes – with hundreds of Indian men volunteering for the Confederate Army. If the Confederacy won and gained its Independence – then Jefferson Davis guaranteed a Treaty with the Indians granting them all the unconquered land to the West, forever. Lincoln (and others like him) viewed the Confederacy as “getting in the way” of White expansionism into the unconquered areas of the West – and as a barrier that needed to be removed by military force. To this end, and in a bid to preserve White (Union) lives, Lincoln authorised the raising of Black Regiments – to be controlled by White Officers and NCOs (although Black soldiers were eventually promoted to NCO ranks). In the extracted provided below, there is a vivid description of these Black Regiments being used against the Confederate Army during 1864 Siege of Petersburg (just after the Union exploded a huge mine under the Confederate lines – killing and wounding hundreds) – written by a Confederate General (Edward Porter Alexander). He reports mass cowardice, some bravery and the despicable behaviour of some Confederate troops whilst dealing with captured Black soldiers. Some Confederate Officers even recognised their former slaves amongst the Union casualties!