‘There were three Floyd County boys wounded – Joseph Fledger, Samuel Evans, and Henderson Booth – another five were slightly wounded, but Fledger lost his right-arm. Evans was struck on the breast – the doctor doesn’t think he will ever get well. The shells flew as thick as hail and burst all around me – but thank god they never touched me yet – they struck so close to me that several times they flew my face full of dirt! We had “14” horses killed – two of them within three or four feet of me! There isn’t any fun in this sort of work – so I won’t say anymore about it.’

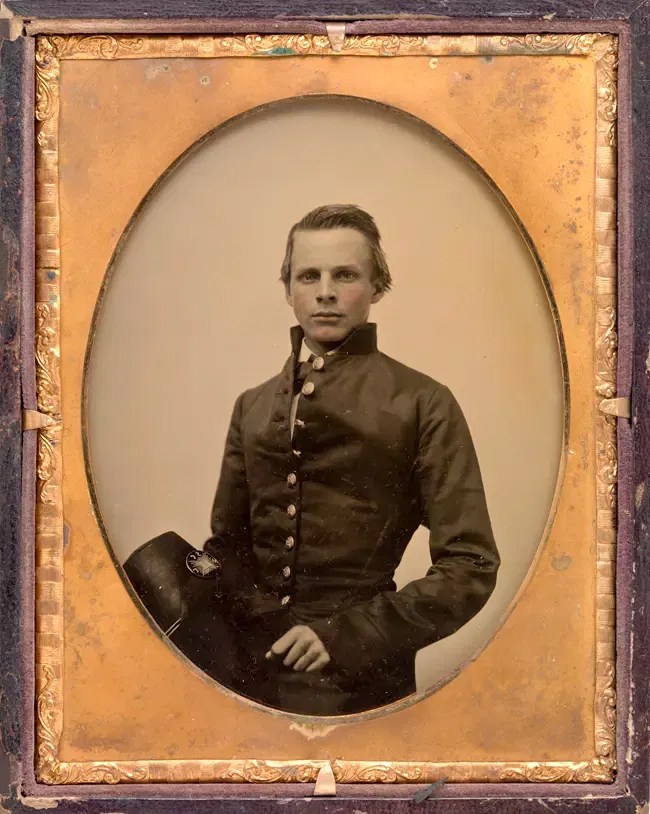

Letter Written By Confederate Gunner “William P Walters” (c. 17.12.1862) Serving Under John Pelham*

The Battle of Fredericksburg occurred on December 11th-15th 1862 in Virginia and was the direct consequence of the invasion of the South ordered by President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was obsessed with demonstrating military dominance and inflicting a quick a decisive defeat upon the Confederate forces. The problem was that despite all the advantages in raw materials, industry and man-power – none of the North’s best Generals were able to deliver on any of Lincoln’s objectives. The embarrassment lay in the fact that Lincoln equated military dominance with moral right – and so far it was the Confederate cause that been achieving all the successes – implying that perhaps Lincoln’s objectives were not altogether worthy of such an easy victory. Certainly, between 1861 and Gettysburg in 1863, the momentum (and moral right) appeared to be with the Confederacy. Even after Gettysburg, it took the much stronger Union a two further years of bitter and intense fighting to finally turn the tide.

The Confederacy had expelled the Union after its attack on Richmond during the Peninsula Campaign (March-July) of 1862, with the Union force retreating out of Virginia (suffering yet another reversal at the Battle of Second Manassas – situated in Prince William County, Virginia – fought between August 28th–30th, 1862). General Lee pursued the Union forces by invading Maryland – followed by the bloody but indecisive Battle of Antielam (September 17th) 1862. General Lee withdrew his more or less intact Confederate army back into Virginia, and this led to Lincoln’s hard-pressed Generals suggesting a daring amphibious assault across the Rappahannock River into the Virginian city of Fredericksburg. Although the Union had been continuously attacking Vicksburg in Mississippi since the beginning of hostilities – at this point in the war, Union forces had been kept firmly out of a Confederate civilian stronghold by a cleverly laid-out network of entrenchments and well-placed artillery. All the major engagements so far had been in the open countryside – but Fredericksburg would change all this.

Indeed, Union troops would successfully traverse the river under fire and quickly establish a strong bridge-head whilst Union artillery deliberately fired upon the fleeing civilians as most of the city was occupied. The Union Infantry entered the urban theatre and shot and bayoneted any civilian (Black or White – man or woman) who got in the way as the Confederates fought a disciplined withdrawal to the other side of the city – an area which could be better protected. Rape, thieving and destruction by fire was the hallmark of this Union attack – which bears very little resemblance to Union rhetoric as to why the war was being fought. Meanwhile, the Confederacy was applying its usual strategy of pulling all available forces to a central point of convergence – depending upon where the Union threat was the greatest. This response drew Confederate forces from other places that needed defending – but which were not yet under attack. These places were left unprotected whilst no threat existed. The Confederacy had to pursue this path as it did not have access to the extent of manpower held by the North. This is why the Union forces were allowed to establish a bridge-head in Fredericksburg experiencing only a light snipping from the Confederates.

Believe it or not, despite a poor start, General Lee would gather his forces and once again inflict an embarrassing defeat upon the Union. Although Captain John Pelham was in-charge of at least 18 artillary guns that comprised the Confederate Horse Artillery (light artillery guns, crew, ammunition and equipment – designed to be moved quickly around the battlefield by teams of horses – as part of the cavalry for quick redeployment) – General Lee was reluctant to send these valuable assists forward to fill a gap in the Confederate lines (on its right-flank) as the emboldened Union forces prepared to advance en masse from their bridgehead on December 13th, 1862. John Pelham asked permission to be allowed to take just one of his artillery guns – a light, smooth-bored Napoleon (together with an experienced field crew) into the gap – where the fast-reloading and rapid fire could cause untold trouble to the advancing Union forces. As he was about to set-off, the British observer – “Captain Lewis Philips” – presented Pelham with his Grenadier Guards Regimental neck-tie for good-luck, which Pelham tied around his hat. Leading his men into battle, Pelham instructed the “Creole” crew to lay-down on the ground between loading, firing and receiving return fire – to preserve their lives as long as possible. The intensity of fire this “Creole” crew laid-down hindered, stopped, and delayed the Union advance long enough for the main Confederate forces to be brought into action in that part of the field (an intersection on the stage road that led toward Richmond).

John Pelham, when he trained at West Point, was renowned for his pugilistic-skills (bare-knuckle boxing) – where he could pepper his opponent with damaging blows from either hand whilst employing lightness on his feet to avoid any counter-blow by never standing in the same place twice. Using this idea of hitting and moving is precisely the thinking behind the Confederate Horse Artillery. Conventional (heavy) or “Foot” Artillery had to be deployed in laborious fashion into set positions before the battle that dominated the field and rarely moved during the battle. Fewer (stronger but slower) horses (usually four) were used to pull much heavier cannon that still needed to be manoeuvred by their crews in and out of position. The Horse Artillery used much lighter cannon and possessed a greater number of horses per gun (usually six) – with the horses trained to quickly position the pieces before being unhitched and moved to the rear. Rapid fire was the order of the day for Pelham and his “Creole” Confederate Cannoniers! They caused havoc with their accurate fire to the Union left-flank before Federal spotters were able to accurately perceive where the fire was coming from and attempt to do something about it.

Despite using good terrain to the maximum advantage, Pelham’s single cannon was still far in advance of the Confederate frontline. Firing at the Union flank meant each cannon-ball smashed through multiple ranks of soldiers – hitting side-on. It was a dangerous gamble – but one which paid-off because Pelham was a competent Officer and his “Creole” crew superb when under fire. A Union Pennsylvanian Infantry Regiment started to take ridiculous numbers of casualties as Pelham’s cannon balls smashed there way through life and limb. However, Pelham only managed to fire three rounds before Union return fire stated coming in. At one-point, as Union rounds were landing, the Louisiana “Creole” crew began to sing the French “La Marseillaise” in defiance. Within minutes, hundreds of Union cannons, both near and far, were returning fire into the general direction, even though the lay of the land often prevented a clear line of sight. The reality was that the Union forces only had to land just one well-placed shot to destroy the single Confederate cannon and neutralise most of its crew. Pelham had chosen his position so well that despite the weight of return fire – the Union artillery found it very difficult to score a direct hit.

A single Confederate “Creole” named “Hammond” was struck and killed by a deflecting Union shot near the beginning of the exchange (sponging down the cannon) – whilst most Union fire either landed short or flew far over-head. Pelham’s fire caused Union Officers to assume that at least “8” Confederate cannons (two Confederate batteries) were holding-up the Union advance – but in reality Pelham was out-numbered on the day 30-1 – as he was opposed by “5” Union batteries (each Union battery being comprised of six guns). Pelham kept on firing – hitting Union cannons and ammunition dumps. Union ranks were bowled-over into bloody heaps. Caring for his “Creole” crew – each man had to lay flat on the ground when not engaged in the act of firing. Even then, at least one gunner lying on the ground had his head blown-off by a Union shell. On the day, John Pelham and his “Creole” crew were watched and admired by thousands as they worked their single-gun. This bravery and defiance was produced by one “White” Officer and a handful of “non-White” men in the service of the Confederate army.

As the Union managed to move up small groups of troops around Pelham (destroying Confederate reinforcements sent to assist the single cannon) – the danger increased moment by moment. Pelham was still sat atop his horse guiding the battle when a Union shell struck and killed one of his gunners and wounded several others. He dismounted to check on the well-being of his men. Meanwhile, the Confederate General – JEB Stuart – sent numerous messages requesting Pelham withdraw, all of which were ignored. The third such message read “Get back from destruction you infernal gallant fool – John Pelham!” Still the “Creole” crew continued to aim and fire – single-handedly keeping an entire Union army at bay. As it took “9” men to service the gun – so many of Pelham’s soldiers had been killed that he now had to assist with the process to keep the gun operational. Corps Commander Stonewall Jackson then sent a direct order that Pelham must retire with what was left of his crew.

As Pelham had now run-out of ammunition – he ordered the single cannon hitched to the remaining horses and retreated back to the safety of Hamilton’s Crossing with his brave “Creole” crew. Unaided, Pelham’s single cannon held up the advance of at least one-third of an entire Union army for around one hour. General Lee, watching this action through field-glasses from afar, commented “It is glorious to see such courage in one so young” – when told the Officer was John Pelham (I wish he had acknowledged the bravery of the “Creole” crew). After his engagement with just a single cannon – Pelham (and his men) went on to command “15” artillary pieces in the further Battle of Fredericksburg that saw an entire Union army decimated as it advanced with a great purpose and discipline – maintaining pristine ranks of well-armed and trained men (Meade’s Pennsylvanian Regiment). Pelham’s Cannoniers continued to fight (and die) with incredible bravery.

The point I want to make is that the men who risked and lost their lives during this glorious battle were not “White”, or at least were not ONLY White. These Confederate soldiers were mixed-race, Black, and/or Native American – many imbued with the Socialism of Old France (even their cannon was “Napoleon”). I am told that there are many such examples of this type of bravery by “non-Whites” serving in the Confederate army. My task is to seek-out these stories and make a record of them. Perhaps the final irony is that whilst the Confederate army had Black, Chinese, Creoles, Mexicans, and Native Americans serving in it since its inception in 1861, by the time this battle occurred in 1862 – it was still illegal in the “Federal” United States for non-Whites to join the Union army! Such is one of the many ironies that permeates the history of the American Civil War.

English Language Reference:

John Matteson, A Worse Place Than Hell – How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation, Highbridge, (2021), Audible, Chapter 10 – Pelham Does First Rate*

Online Reference:

https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/john-pelham/