When Northern President Lincoln ordered (Union) General McClellan to take the well-dressed, armed, and trained “Army of the Potomac” and invade the Southern Confederacy via Virginia (during the 1862), Lincoln also ordered that the US Balloon Corps (inspired by the work of Thaddeus Lowe – and which possessed at least “seven” balloons), send a balloon to General John Wool at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Initially, this was to keep an eye on the movements of the much-feared Confederate State’s Ship (CSS) – the ironclad “Virginia” – which was stoically prowling the nearby waters. The mission of this balloon was to aeronautically “observe” the ironclad – and gather information not attainable by any other means. The balloon in question arrived on the 15th March 1862 – but despite being taken-up several times – saw no trace of the “Virginia” (or the nearby Confederate Army).

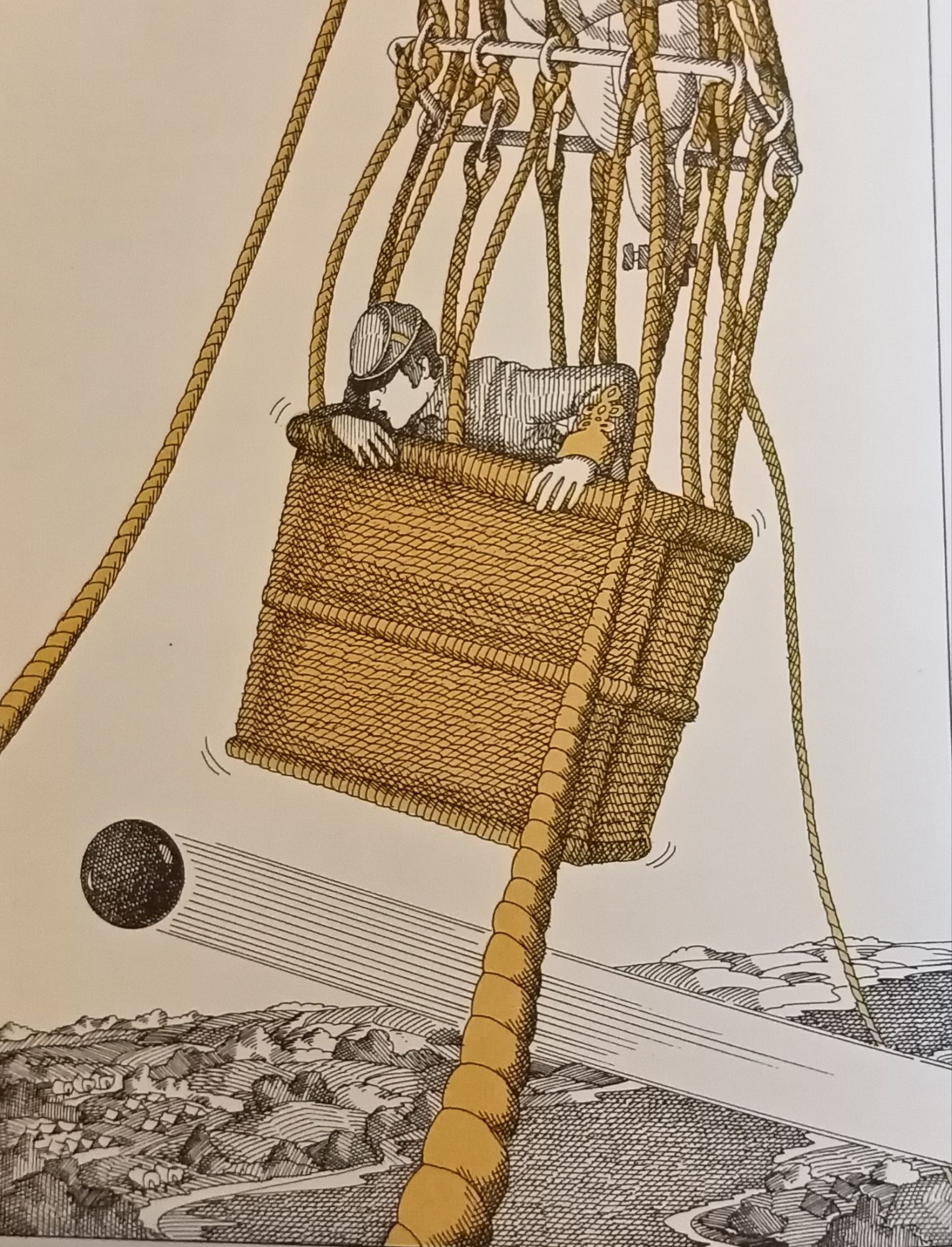

This is how the vagaries of balloon warfare began in Virgina that would lead to the hostilities known as the “Peninsula Campaign” (fought by the North and the South between March-July 1962). Although these Union balloons were “unarmed” – Confederate gunners often resented the fact they were being observed from above – inviting pot-shots from every rifle and gun below. Every time a Union balloon came into sight – it offered Confederate gunners an opportunity to practice their gunnery skills – the first known incident of “flak”! The Confederates developed a tactic for shooting at the balloons by laying-down a field of fire designed to hit the balloon as it took-off – or when it was about to land. This is similar to the technique taught to modern anti-aircraft-gunners when engaging hostile targets (which have no choice but to “fly-through” the sheet of fire).

Confederate fire did score near misses but few direct hits. Shrapnel sometimes struck the baskets of Union balloons at the Battle of Seven Pines – as shells passed between the mooring lines. The Confederates did claim to have shot-down a Union balloon on the Peninsula. On 20th June 1862 – the “Atlanta Southern Confederacy” newspaper announced under the headline “Abe’s Balloon Plugged” – that a Federal balloon was brought down when a shot from Purcell’s Battery struck the device and tore it to pieces. This story (and others) is unsubstantiated, as there is no record of any Union balloon being shot down. Furthermore, when the Union Balloon Corps was disbanded in 1863, it allegedly still possessed all its balloons. Of course, post-war Union propaganda might be at play here, as “Reconstruction” often meant the re-moulding of ideas as well as physical structures. The Union would not allow the Confederacy (even in retrospect) to appear to be winning in anyway.

In the early days of the Peninsula Campaign, the Confederates also developed an “Aeronautical Balloon Corps” – although the (two) Confederate balloons – the subject of a popular (semi-fictionalised) storybook by Burke Davis – were “make-do” affairs. As a response to the Union Army Balloon Corps, the Confederate Army created its own smaller balloon corps in the spring of 1862. Captain John Randolph Bryan supervised the construction and deployment of an (as far as I can tell) “unnamed” surveillance balloon. Captain John Randolph Bryan was the CSA’s first untrained (volunteer) “Aeronaut”. He risked his life twice in a ramshackle affair – which he had designed and built with limited knowledge and resources – but it did its job.

He wrote, “I have never even seen a balloon, and I knew absolutely nothing about the management of it.” The cotton balloon was coated with varnish and filled with hot air, rather than hydrogen, because the Confederate Army did not have the equipment to generate hydrogen on the battlefield.

Bryan launched his balloon on 13th April 1862, over (the famous) Yorktown, Virginia. During the flight, Bryan sketched Union positions. However, on the next flight (described in some sources as occurring “at night”) – Bryan was forced to cut off the tether linking his balloon to the ground after a Confederate soldier became entangled in it. During his free flight, Confederate troops fired on the balloon – believing it belonged to the Union Army. Bryan, however, escaped and landed safely. In order to reduce the likelihood of having a balloon brought down by gunfire, the Confederate plan had been to harness horses to the guide wires for extra-security. At a signal from the aeronaut, the horses would forcibly pull the balloon out of the sky and down to safety on the ground.

The second Confederate balloon was code-named “Gazelle” – and was filled with hot-air garnered from the Richmond Gas Works. It was constructed in Savannah, Georgia, by Langdon Cheves, who used his own funds for the project. Although the balloons of the Union Balloon Corps were made of white silk (and coated in a varnish) – Cheves did not have access to the same supplies. In a writing in the South Carolina Historical Magazine, author J. H. Easterby explained, “…Mr. Cheves designed and superintended the construction at the Chatham Armory in Savannah, chiefly at his own expense (I believe), made of ladies dress silk bought in Savannah and Charleston, in lengths of about 40 feet and of various colours.” This material was sewn together and varnished to create this second Confederate war balloon.

This multi-coloured patchwork (of various materials) generated the nickname by which it was often known – the “Silk Dress Balloon.” This construction even brought about rumours that followed the balloon well after the war. James Longstreet wrote, “A genius arose for the occasion and suggested that we send out and gather together all the silk dresses in the Confederacy and make a balloon.” This semi-true story was often repeated in various post-war writings. Burke Davis, in his 1976 book on the matter is of the opinion that the women and girls of Richmond donated their finest dresses – AND assisted the Confederate war-effort by carefully sowing this material together to create the “Gazelle”! I note a general confusion in American sources regarding this history which I assume is a deliberate post-1865 attempt at sullying the history of the Confederacy by the Northern victors. Perhaps the women and girls of Richmond assisted the created of the “first” Confederate balloon flown by Captain John Randolph Bryan in what was “emergency conditions” – as their homeland had been invaded by the Yankee foreigners. Overtime, the circumstances surrounding the development of the two Confederate balloons became entangled and confused.

Once constructed and sent to Richmond, the “Silk Dress Balloon” was handed over to General Edward Porter Alexander – the second Confederate aeronaut – in order to begin his duties (as he valued the potential of aerial observation). In his memoirs, General Alexander explained, “We could not get pure hydrogen gas to fill the balloon, & had to use ordinary illuminating gas, from the Richmond Gas Works…” This gas, created from coal, was primarily used to light gas lamps in homes and on streets throughout the city of Richmond. After the balloon was filled in Richmond, it was attached to a train car and moved to the front. Alexander made his first observations during the battle of Gaines Mill, from which he was able to observe Union troop movements – and signal this vital information to his fellow (CSA) Officers.

For safety reasons, the Confederates decided to transport their balloon via the water when not in operation (to protect it from enemy fire). The silk balloon was loaded onto the armed (CSA) tug “Teaser” – to transport it from the Richmond Gas Works up to the front-lines along the James River. This system, however, eventually led to the demise of the Gazelle. The Teaser, loaded with the Gazelle, ran into Union Naval Forces patrolling the James River, and was fired upon and captured by the US Marines carried aboard the USS Maratanza. The Confederate balloon was given to the Union expert – Thaddeus Lowe – who cut it up into scraps to give as souvenirs. Some of these pieces are still in existence. The Union lost the Peninsula Campaign due to a lack of reliable military intelligence. The Confederate Aeronautical Balloon Corps was abolished on the 4th July, 1862 – following the retreat of Union Forces out of the South.

Although suffering no great defeats in the field – the Union Army was unable to inflict any decisive defeats upon the Confederate Army. Indeed, US General McClennan was of the mistaken opinion that his army of around 90,000 was greatly out-numbered by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia (commanded by Robert E Lee) – when in fact the two forces were about equal in number. General Lee carefully countered and repulsed each Union attempt to advance to Richmond – until the will of the North was broken and its morale deflated. The Union withdrew from the South to preserve its forces and protect Washington from a potential counter-offensive by the Confederacy.

English Language References:

https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/most-fashionable-balloon-civil-war

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/civil-war-ballooning

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8640058/john-randolph-bryan

Davis, Burke, Runaway Balloon – The Last Flight of Confederate Air Force One, Coward, McCann, & Geoghegan, Inc, New York, (1976)

Sears, Stephen, The Gates of Richmond – The Peninsula Campaign, Recorded Books Whispersymc, (2013)