The order and discipline that defines the British Army – in its many guises throughout history – stems from the unbridled fighting spirit of the indigenous Britons (Kelts) – and the rank-and-file order that defined the fighting prowess of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Added to this might be the fighting experience of the Vikings and the various Germanic tribes that invaded and settled the British Isles. The Picts might be added to this list as aa mystery still remains as to their origin. The Normans, of course, were Franco-Vikings who brought with them the notion of the “Permanent State” and an extensive castle building programme. All this different and distinct cultural experience became historically funnelled into the “New Model Army” – designed by Oliver Cromwell – which fought for Parliament in its battles against the Royalist Armies of King Charles I during the English Civil Wars of the 1640s.

The New Model Army secured victory for Parliament and changed the face of British politics forever. Oliver Cromwell, as “Lord Protector”, died in 1658 where his son (Richard Cromwell) inherited this role. In 1660, however, a Kabel of counter-Revolutionary conspirators in England forced Richard Cromwell out of Office and prompted Parliament to accept a limited “Restoration” of the British Royal Family hitherto exiled in France. This led to King Charles II assuming the throne in 1660 – but this was only an exercise in rhetoric. Parliament retained all political power it had won the day the Executioner’s axe fell on the neck of King Charles I in early 1649 – whilst employing King Charles II merely as a “Constitutional Monarch”. This made His Majesty nothing but a paid “Civil Servant” with no real (or substantive) political power. This is essentially the political system the UK still retains today.

During the English Civil Wars – a pro-peasantry Bourgeois Revolution successfully occurred within England. Around 200,000 British people died in the fighting to abolish an “Absolute Monarchy” and instigate the rule of a democratically elected Parliament in its place. The 1660 “Restoration” changed none of this outcome – even though a form of deception was often used to suggest otherwise. Whereas Cromwell intended to instigate a countrywide literacy project throughout the peasantry – and build hospitals and better housing, etc – the Bourgeois Parliament of the post-1660 era firmly rejected the well-being of the peasantry and instead aligned itself with the cultural norms and privileged expectations associated with the Aristocracy – the political power of which it had so violently usurped. With the return of King Charles II – the “New Model Army” was “dissolved” – but the extent to which this was actually carried-out is open to debate – as it seems that many Regiments voluntarily confined themselves to Barracks. As Parliament lacked any other armed-agency to enforce its will – this situation was simply permitted to exist.

As matters transpired, five Regiments (some reconstituted “Royalist” formations) volunteered to form a strictly “Ceremonial Guard” to act in self-defence of the Royal Family was employed by the British government (albeit very high rate). The new King – and his “Guard” – were subordinate to the will of the elected British Parliament and did not yet form a national fighting force. Although the “Guard” showed deference to the King – their orders were always issued by the Parliamentary Authorities. Indeed, the soldiers possessed “Standing Orders” to protect the Royal Family from any unauthorised external attack – and to arrest and report any member of the Royal Family – should they attempt to exercise any independent control of the “Guard” itself.

At this time, England possessed no formal army. The former (resting) Regiments of the “New Model Army” eventually volunteered to join the “Ceremonial Guard” of the Royal Family that became so large – that the British Parliament was forced to recognise its existence. This led direvtly to reform of what became known as the “British Army” (note – not the “Royal” Army) – the function of which was to maintain the status quo (as there was not yet a professional Police Force), defend the British Isles from external attack, represemt British interests abroad (Cromwell had fought in Eire and Scotland, not to mention Wales), and take turns in the “Ceremonial” guarding of the now powerless Royal Family. This new “British Army” was a permanent institution that required struct discipline and order if the populace was to tolerate its existence.

Prior to ths time, armies were only raised in England when they were required, and were almost always amateurish in nature (a father, usually a farmer, would teach his son how to fire a bow, use a staff and knife, and learn how to kick, punch, grapple and throw, etc) – comprised of called-up (or conscripted) populations of male peasanry – deriving from the various shires of the kingdom. An able-bodied man could walk, stand, run, and fight when need be (his heart, chest, eyes, ears, and feet, were not tested). There was no modern sense of physical “fitness” as such, or of disability effecting fighting prowess. The modern (post-1660) “British Army” slowly changed this attitude – and effectively abolished the enforced call-up of fighting farmers. In-turn, this led to the slow loss of English martial arts as used on the battlefield of (feudalistic) mass infantry affairs. Such English martial arts evolved into the individualistic fighting sports of Wrestling, Boxing, Fencing, Archery, and Duelling with Pistols, etc. It would still be over 250-years until modern fitness would permeate military thinking – but the modern British Army sought to replicate the stoic discipline of the Greek and Roman Armies – albeit armed with fire-arms.

The mind and body had to be subordinated to the vigour of military discipline. Standing still for hours – juxtaposed with marching tens of miles carrying pack, weapon, food and ammunition, had to all be performed with equal determination during the day, the night, the sun, the wind, the snow, or the rain. Such is the expertise of the “British Army” – one of the greatest armies in the world! Strict discipline flows from top to bottom in the “British Army” – and obedience manifests upwards from the bottom to the top. Discipline must be maintained regardless of what the soldier is experiencing within (thoughts and feelings) and without (the existential physical conditions which can be extreme during battle). A calm and central position of being must be assumed by the “British Army” soldier – as he condenses within his mind and body the power and will of the British State. The notion of “Rank” is designed to facilitate this order and generate a channel through which all the experience of training can be generated and distributed. In times of combat – the efficient use of “Rank” permited the prudent use of movement and stillness – an ability which saveed lives and ensured victory. What follows below is an examination of the foundational “Ranks” originally used in the “British Army”:

General: A “General” is in fact a “General Officer”. This suggests that these “Officers” are responsible for “General” duties and responsibilities involving command and control. Today, many high-ranking “Generals” are in control of the Administrative aspects of an army. Vast bodies of men are reduced to numbers on a page, or a unit marked in a column. However, if the original function of a “General” is derived in the modern “British Army” from the “New Model Army” – then what Major RM Barnes has to say is vitally important:

“An interesting point is that this force was commanded by Captain-General Sir Thomas Fairfax. The cavalry was under Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell, and the infantry under Sergeant-Major-General Skippon. This is the explanation of the familiar conundrum, “Why is a Lieutenant-General senior to a Major-General?” The answer is (a) The Major-General was originally a Sergeant-Major-General; and (b) the Lieutenant-General commanded the cavalry, which was the senior branch of the service.”

A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army, Seeley Service & Co, (1954), Page 21

General Officers:

Captain-General

Lieutenant-General

Sergeant-Major-General

Designations of Ranks and Units Below General:

Field Officers:

Colonel: Itialian “colonello” = literally a “little column”. Originally, the “little column” represents the “Headquarters” (HQ) – situated at the front of a Regiment. Whilst on the march – or in position – a “Colonel” leads from the front (at least in theory).

Major: Latin – from “majour” or “magios” – meaning “greater”, “effective” and “leading”. Although a “Major” in the early “British Army” is the lowest rank of “Field Officer” (those who liaise between Company Officers and General Officers) – such a rank is “above” those ranks worn by “Company Officers” – the latter of which always work (and associate) with the enlisted men.

Company Commissioned Officers:

Captain: French – “Capitaine” – which translates as “Head” or “Leader” of a “Company” or similar small unit. This correlates with the similar Roman rank of “Centurian” – an Officer in-charge of the welfare and command of one hundred men.

Lieutenant: French – “one who acts as a substitute” for a “Captain”, “Colonel”, or “General”, etc.

Ensign: French – “Ensigne” – meaning “flag”. This originally referred to a flag-bearer in the infantry (and “Dragoons”) which is today replaced by the rank of “2nd Lieutenant”. In the Cavalry, this rank was referred to as a “Cornet” – referring to a “2nd Lieutenant” who played a trumpet-like instrument during parades – or in battle. Flag-bearing and rousing music was once very important for troop morale.

Subaltern: French – “Subalterne” – literally “inferior” or “subordinate” – usually to a “Captain”.

Adjutant: Latin – “adiutans” – literally “assisting”. This is not a rank per se – but rather a “Post” or “Appointment” (the holder will possess a suitable rank). Interestingly, in the French Army a Platoon Commander is referred to as an “Adjutant”.

Company Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs)

Sergeant: Originally from the Latin – “Serviens” (or “Servient”). Derived from the French – “Sergens” – literally to “serve” – or duty-bound to participate in the act of “serving”.

Corporal: French – “Caporal” – related to the Italian term “Capodi” – pertaining to a number of “Heads” (plural) of Sections. Although not directly related to the Latin “corpus” (body) – a “Corporal” is the “Head” of a body (“Section”) of men. As a “Section” consisted of perhaps 6-8 men – the onus regarding Section Heads is that there will be “many” such NCOs within a Company of men (at least 100-strong). Later, the rank of “Lance Corporal” was created to serve as a “Second-in-Command” of a Section – under the control of a “Corporal”.

Soldier: Latin – “Solidus” (or “Shilling”) as in “Solid” currency or “Coinage” – refers to a man who serves in an army for “pay” (“Solde”) – in that he “Sells” his military services. In the British Army, a Recruit was paid one-shilling per day – and was granted the “King’s Shilling” (one-shilling in advance when he formerly joined the Briitish Army) – given-out by the Recruiting-Sergeant.

Private Man: Until the end of the 17th century – this rank was referred to as a “Private Centinel” – that is one man out of a hundred men (that formed a “Company” of soldiers). Such an individual was responsible for himself only – possessed no authority – and had only to obey orders from above. A “Private Centinel” possessed no responsibility for the welfare or actions of other soldiers. As one man would often “Stand-Guard” at various times – he was referred to by the word “Sentry” – a term which has survived into modern usage.

Military Formations

Infantry: Latin “Pedites” – literally “those who fight on foot”. Within the feudal and medieval systems of social organisation – the Aristocrats rode high on horse-back, were held high in the saddle above the masses, and were considered “Majors” (“Superior”) over those who possessed no social rank, no armour, no status, and no horses. The ordinary (peasant) men used roughly constructed weaponry and fought on foot – often in bare-feet in the old days. Despite all these incapacities, these farmers practiced martial arts which saw fathers and uncles pass-on their fighting knowledge to their sons and nephews. When they were called-up by their King – they had no choice but to fight for free simply because it was their duty to do so. It is incredible to consider that many of the great battles fought by the British prior to the English Civil Wars – were fought, won and sometimes lost (losing tens of thousands in the process – due to the brutal nature of the fighting) – by ordinary farmer-warriors who worked the land owned by their over-lords. It was Oliver Cromwell who invented the idea of recruiting soldiers who were paid, clothed, fed, properly armed, trained, and professionally led.

Company: For many centuries the “Company” used to be the main organisation of around 100-120 men which was commanded by a “Captain” who liaised with the Lord in authority. Companies were moved in co-ordination so as to direct massed infantry assaults. On occasion, “Mercenaries” did form a “Company” which like today symbolised a “business” – and rented-out their battle-expertise to the highest-paying Monarch. Indeed, this is probably the origin of the term. Soldiers learned to manoeuvre in “Company” formation. It was not until the “Half-Company” and “Platoon” system of the Swedish Gustavus Adolphus (1594-1632) started to permeate the “New Model Army” of Oliver Cromwell – and saw the “Company” divided into smaller units as fire-arms became more readily available and killing at a distance the norm. A “Company” that could be efficiently sub-divided – could be more readily directed around the battlefield to out-manoeuvre the enemy. The British Infantry became masters of this type of fighting.

Battalion: Latin – “Battuere” – or “to strike”. This is linked with the Latin – “Battalia” – which refers to a unit of men correctly lined-up in battle array – usually consisting of four “Companies” or around 500-men.

Brigade: Latin – “Brigata” – a “formation” which is linked to the Latin – “Brigare” – which refers to “fighting”, “striking”, and “fighting”. A Brigade might be comprised of three Battalions and around 1,500 men.

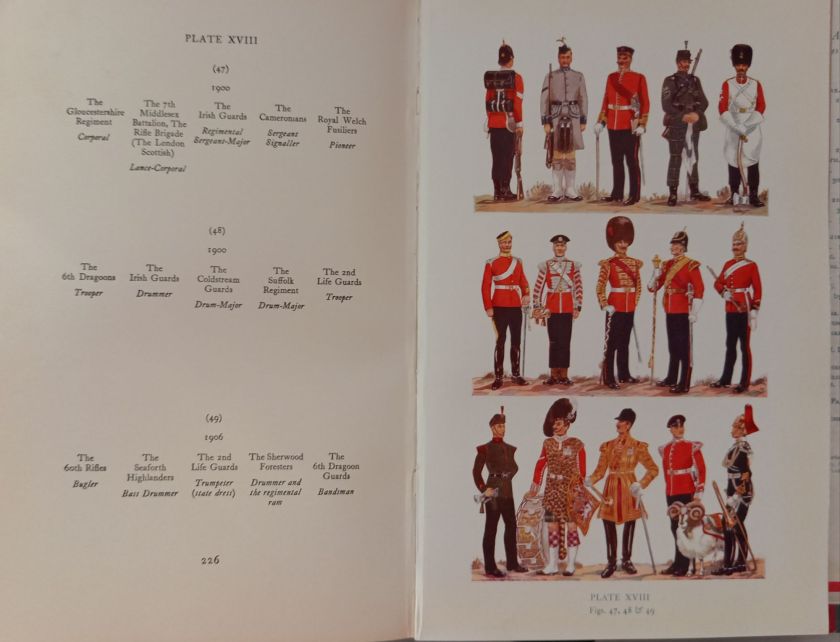

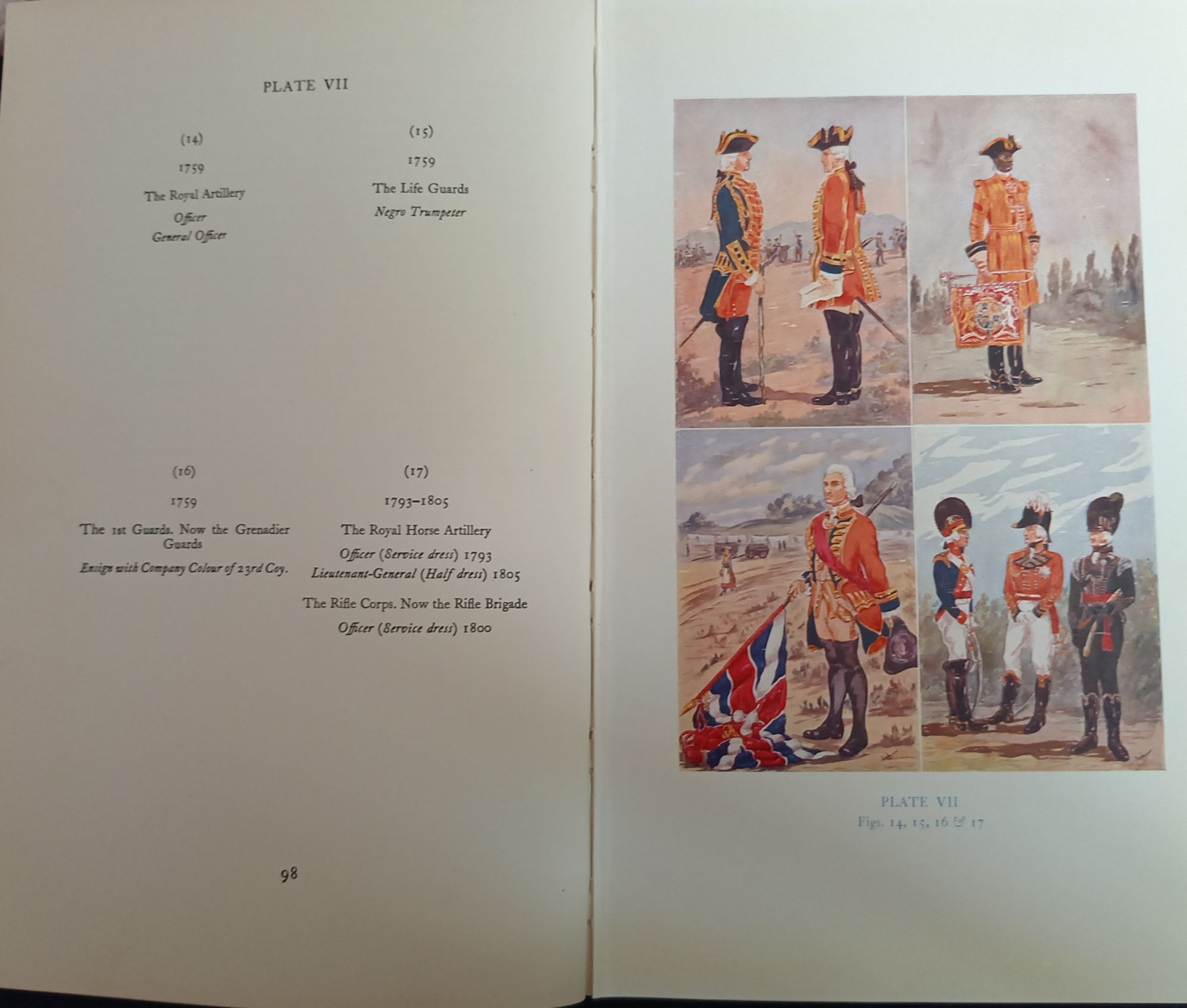

Regiment: From the Latin “Regimen” meaning “Order” and “Rule”. Originally, a formation linked to a specific location of recruitment and a shared battle history. However, Regiments in the British Army appear to have developed fully after the Restoration of 1660 – but include military formations previously referred to as “Cavalry”, “Guards”, and “Artillary”, etc, sometimes identified by their “Battalion” designations (a habit that still exists today) as each Regiment numbered around 650 men – just over that of an average “Battalion” – although more than one “Battalion” can be a member of a “Regiment” (particularly following the 1881 amalgamation). There are a number of exceptions to this observation. In 1571, for instance, Queen Elizabeth I raised the “Holland Regiment”. Monck’s Regiment of Foot served the Parliamentary Cause during the English Civil Wars and is today better known as the “Coldstream Guards”. The “Royal Regiment of Guards” fought for King Charles I during the English Civil Wars and is today known as the “Grenadier Guards”. It seems that early examples of the use of the “Regiment” designation might have included newly formed units with no fighting history or direct links to a British geographical location. These attributes had to be earned through blood and honour. However, eventually very well-establish military units seem to have voluntarily taken on this designation – or been given it by the British government.

English Language Reference:

Major RM Barnes, A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army, Seeley Service & Co, (1954), Pages 21-23