Translator’s Note: This article was written in distinct research layers, and had a number of titles (and versions) as I discovered new information within Russian and Chinese research sources. The extant English language versions of this story remained very basic, and did not offer much cultural or historical context. What is certain is that this Chinese palace in Southern Russia is around 2000 years old, and is the direct consequence of the interaction between the Han Chinese and the highly militarised multi-ethnic (and multi-racial) group referred to by the Chinese as the ‘Xiongnu’ (匈奴), often translated as ‘Fierce Slaves’, or ‘Fierce People’ – with the implication being that their ‘fierceness’ was a direct consequence of their assumed ‘primitive’ culture and behaviour. The Xiongnu dominated Northern China and the Russian Steppe for centuries from at least the 3rd century BCE, and were often able to invade China and defeat its military forces from time to time. From around the 1st century CE, the Xiongnu split into two distinct groups, with the ‘Northern Xiongnu’ heading into Southern Russia (out of Mongolia) and away from Chinese influence, and the ‘Southern Xiongnu’ moving out of Mongolia (southward) toward Northern China, and becoming a vassal State of the Eastern Han Dynasty. Some researchers within China have linked these Sinotised Xiongnu with the Hakka ethnicity. The palace in question was built in Southern Russia prior to the split of the Xiongnu, and seems to represent an imperial Chinese presence in that area, although the archaeological record does not support a wide-spread or long-lasting presence of Chinese culture in that region (which was then controlled by the Xiongnu). European ‘Vikings’ (from Sweden) did not colonise Russia until at least the 9th century CE, and by that time, the imperial Chinese presence had long disappeared. Although there are competing theories as to ‘why’ this palace was built, it is generally agreed that its architectural design is typical of the Western Han Dynasty. Prior to the Qin and Han Dynasties, all non-Han Chinese groups living to the north of China were officially referred to under the collective term of ‘胡’ (hu2), which literally means ‘wild’ people. It is thought that the term ‘Hun’ may have derived from this ideogram. Alternatively, Chinese sources also state that during the Middle Han Period, the term ‘Xiongnu’ (匈奴) was pronounced ‘Hiungno’, and became shortened to ‘Hun’ over-time. Whatever the case, in 303 CE the Northern ‘Hun’ entered Eastern Europe and became known in the West for their fighting prowess. ACW 21.4.2017

Within Russian language sources, this apparent Western Han Dynasty example of Chinese architecture is referred to as the ‘Ташебинский дворец’, or the ‘Tashebinsky Palace’ (often termed the ‘Tashebik Palace’ in English translation). This takes its name from a river that flows nearby the city of Abakan, which is situated in the Southern Siberian area of Khakassia. Khakassia is 2,446 km from Beijing – a distance that cuts diagonally through Mongolia. The ruined structure of the Chinese palace itself, is situated 8 km south of Abakan city:

During the construction of a road in 1940, the Soviet Authorities discovered these unusual buried ruins, and in the subsequent archaeological dig (carried-out between 1941 – 1945), an impressive Western Han Dynasty palace was uncovered. What is remarkable about this find, is that its excavation occurred just prior to, and during the disastrous Nazi German invasion of the Soviet Union – which sparked the Great Patriotic War (a self-defensive war that cost the Soviet people around 40 million casualties). Nevertheless, despite the chaos to the west of the USSR, Soviet archaeologists carried-out their work methodically and without error. Within Chinese language sources, this find is often referred to as the ‘阿巴坎宫殿’ (A Ba Kan Gong Dian), or ‘Abakan Palace’, with the excavation recorded as happening between 1941 and 1946 (this is probably due to the differences between the lunar and solar calenders). As China was also fighting a war of self-defence against a vicious Japanese imperial enemy at the time, there was no direct Chinese academic input, but the Soviet results are very carefully translated into the Chinese language and readily available upon the Chinese internet.

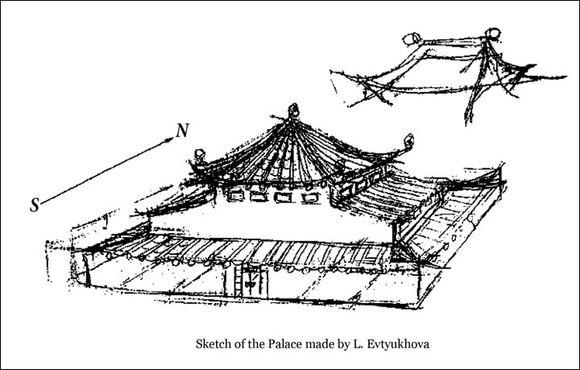

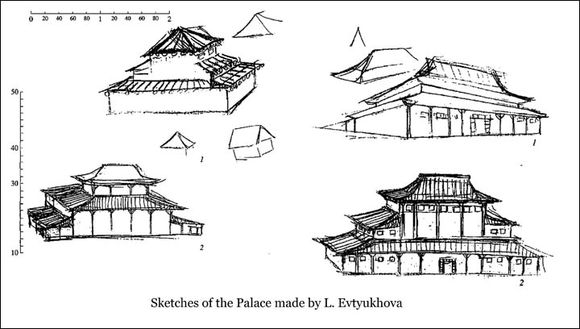

The excavation was led by LA Evtyukhova of the State Historical Museum and VP Levasheva of the Minusinsk Museum of Local Lore. As the dig progressed, Soviet archaeologists realised that this was a unique and very rare structure in Russia. It was dated to be around 1st century BCE, and appeared to be of Western Han Dynastic design. Chinese language sources also report that this is the northern-most example of early dynastic Chinese architecture ever found, existing as it does far outside of the borders of Northern China. This three-storey palace was built upon a levelled (stamped mud) platform of 1500 м², with a main entrance facing southward (meaning the structure was aligned with the cardinal points, typical of Feng Shui requirements, for example). The length of the building (east – west) measured 45 meters, whilst its width (north – south) measured 35 meters. The central structure comprised of a large square hall (measuring 12 m by 12 m within Chinese sources – but described as 132 м² in Russian sources), whilst the palace itself was comprised of 20 rooms each measuring between 28-30 м² (with many of the walls being around 2 m in thickness). The floor consisted of sandstone slabs laid over a mud (or ‘clay’ floor) that contained pipes or channels – designed to distribute warm air generated in a furnace (thus warming the floor), whilst the support pillars, doors, roof rafters, lintels, and mats were all made of wood. Many of the rooms also appeared to have been heated independently by braziers, with flue pipes pumping fumes out of the palace. Clay tiles decorated the main entrance containing pagoda (or ‘Xmas tree-like’) designs, whilst the door to the central hall possessed massive bronze handles depicting a horned demon wearing a three-pointed crown. A ring through the nose made the ‘door-knocker’.

Round roofing tiles covered the palace containing Chinese ideograms. The Chinese inscription on these tiles reads: ‘Son of the divine-sky – a thousand autumns and ten thousand years in the spring of joy without grief’ (天子千秋万岁常乐未央 – Tian Zi Qian Qiu Wan Sui Chang Le Wei Yang). This choice of words suggests the occupant believed himself to be a divine emperor.

Chinese sources state that the leading Soviet archaeologist for this dig was ‘CB Kiselev’, and that the dig was not continuous, but rather happened in distinct stages in the years 1941, 1945 and 1946. It was CB Kiselev who first put forward the idea that this palace might have belonged to Li Ling. It is believed that following his capture (and/or defection) to the Xiongnu in 99 BCE – the Han Dynasty general Li Ling (李陵) established an imperial-style palace in what is today Russia. The Xiongnu (匈奴) were a nomadic people who were highly warrior-like and aggressive in nature – their Chinese-given name meaning ‘fierce slave’ to denote their perceived cultural inferiority to that of the civilised Han Chinese. In Russia (and throughout the West’), the Xiongnu are known as the ‘Hun’, and are thought to be the multi-racial peoples that eventually settled in the geographical area known as today Hungary. The Xiongnu attacked riding very tough and fast steppe ponies, and would hit various out-posts of Northern China with incredible speed and stealth. General Li Ling had been tasked with the mission of leading a vast Han army to combat the Xiongnu – but his army suffered a terrible defeat. However, the Xiongnu respected Li Ling and took him into their tribal structure – making him one of many Chinese officials who changed sides and worked for the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu chief – known as ‘Chanyu’ (单于) or ‘Single Leader’ – allowed Li Ling to marry one of his daughters, and this made him a Xiongnu lord. However, as Li Ling was unpopular with Chanyu’s mother – he was sent far north to live until her death. The Han Dynasty palace at Abakan may well have been the place purposely built for Li Ling to have lived. However, although a logical assumption, there are no inscriptions linking the Abakan Palace to Li Ling. Another problem is that of the existing Chinese inscriptions that refer to the apparent owner of the palace as an ’emperor’. This is odd as Li Ling was only a general in China, and a lord related by marriage to the Xiongnu leader (Chanyu). He was never emperor of either the Xongnu or the Chinese people – and yet the architecture fits-in with the lifetime of Li Ling. This discrepancy in inscription has led to another Russian theory (formulated by A.A. Kovalyov) which places the Abakan Palace slightly further forward in time – at the beginning of the Eastern Han Dynasty. This version of events refers to one ‘Lu Fang (盧芳)’ – who contested the newly restored Han emperorship during the Guangwu era (24 CE – 57 CE). If this story is correct, then the Abakan Palace would be dated to the 1st century CE – but Russian and Chinese scholars tend to agree that the architecture is firmly of the earlier Western Han type. Certain Chinese language sources also appear to associate both Li Ling and Lu Fang with the same palace – with perhaps Li Ling founding the structure, and Lu Fang living in it (and adding the imperial inscription) at a later date. However, Chinese academics Guo Moruo (郭沫若) and Zhou Liankuan (周连宽) doubt these two explanations, and instead offer the idea that this palace might have been the residence of ‘Xu Bu Ju Ci Yun’ (须卜居次云) – the eldest daughter of the Western Han Dynasty beauty Wang Zhaojun (王昭君), who had been sent by the Han emperor to marry Chanyu – the Xiongnu leader – as a means to bring peace to Northern China.

As this palace was surrounded by a fortified wall, the Russian archaeologists E.B. Vadetska (writing in 1999) considers the building to be a settlement relating to a possible Chinese ‘colony’ established in Southern Russia, in the 1st century BCE. Contemporary Russian sources state that the Chinese academic Chen Zhi (Чэнь Чжи) – writing in 1963 – rejected the Early or latter Han Dynasty hypothesis, and instead was of the opinion that the Abakan Palace was built in Southern Russia during the short-lived Xin Dynasty (9 CE – 23 CE) which existed between the two Han Dynasties in question. This dating is linked to a forensic examination of the Chinese script (天子千秋万岁常乐未央) found on the tiles. Chen Zhi notes that the emperor of the Xin Dynasty – Wang Mang (王莽,) – established his capital at Chang’an (長安), and as any names or titles personally used by, or associaed with the emperor were ‘proscribed’ from use anywhere else, the ideogram ‘長’ (chang2) – meaning ‘long’ (and which is used in the place-name ‘Chang-an’) – was not allowed to be used in any other inscriptions. As a consequence, the tile inscription does not use it, even though the idea of ‘long’ is included. This means that due to a Xin Dynasty imperial taboo on the use of the ideogram ‘長’ (chang2), the authors of the tile inscription had to use the alternative ideogram ‘常’ (chang2). This is a significant observation, as the ‘長’ (chang2) ideogram is usually the preferred character when used within general Chinese literature. This research may have been ignored in the USSR at the time, due to the politics surrounding the Sino-Soviet Split.

©opyright: Adrian Chan-Wyles (ShiDaDao) 2017.

Russian Language Sources:

http://dostoyanieplaneti.ru/4692-ashebinskij-dvorets

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ташебинский_дворец

http://archive.is/20120710124344/kronk.narod.ru/library/kovalov-aa-2007.htm

Chinese Language Sources:

https://tieba.baidu.com/p/2841944226

http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_6354cbfb0102uydc.html

https://tieba.baidu.com/p/3703293973

https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-hans/阿巴坎遗址

http://blog.renren.com/share/105984675/13666830193

https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/匈奴